Marcello Musto’s The Last Years of Karl Marx: An Intellectual Biography provides an illuminating glance at the work and life of Karl Marx during the most unexamined period of his life. Musto’s oscillation between Marx’s work and life provides readers with both an intellectual allurement towards research in Marx’s later years, a task facilitated by the 1998 resumed publication of the Marx-Engels Gesamtausgabe (MEGA2) (which has sense published 27 new volumes and expects to conclude with 114), and with a warm image of Marx’s intimate life sure to guarantee both laughs and tears.

The last few years of Marx’s life were emotionally, physically, and intellectually painful. In this time he had to endure his daughter Eleanor’s extreme depression (she would commit suicide in 1898); the death of his wife Jenny, whose face he said “reawakens the greatest and sweetest memories of [his] life”; the death of his beloved first born daughter, Jenny Caroline (Jennychen); and a lung disease which would keep him sporadically, but for substantial periods, away from his work (96, 98, 122). These conditions, among other interruptions natural to a man of his stature in the international workers movement, made it impossible for him to finish any of his projects, including primarily volumes II and III of Capital, and his third German edition of Capital volume I.

The time he spent with his grandchildren and the small victories the socialist struggle was able to achieve (e.g., the more than 300k votes the German Social Democrats received in 1881 for the new parliament) would give him and Jenny occasional moments of joy (98). A facet of his latter life that might seem surprising was the immense enjoyment he took in mathematics. As Paul Lafargue commented regarding the time when Marx had to endure his wife’s deteriorating health, “the only way in which he could shake off the oppression caused by her sufferings was to plunge into mathematics” (97). What started as a “detour [to] algebra” for the purpose of fixing errors he noticed in the seven notebooks we now know as the Grundrisse, his study of mathematics ended up being a major source of “moral consolation” and what “he took refuge in [during] the most distressing moments of his eventful life” (33, 97).

Regardless of his unconcealed frailty, he left a plethora of rigorous research and notes on subjects as broad as political struggles across Europe, the US, India, and Russia; economics; mathematical fields like differential calculus and algebra; anthropology; history; scientific studies like geology, minerology, and agrarian chemistry; and more. Against the defamation of certain ‘radicals’ in bourgeois academia who lift themselves up by sinking a self-conjured caricature of a ‘Eurocentric’, ‘colonialism sympathizing’, ‘reductive’, and ‘economically deterministic’ Marx, Musto’s study of the late Marx shows that “he was anything but Eurocentric, economistic, or fixated only on class conflict” (4).

Musto’s text also covers the 1972 Lawrence Krader publication of The Ethnological Notebooks of Karl Marx, containing his notebooks on Lewis Henry Morgan’s Ancient Society, John Budd Phear’s The Aryan Village, Henry Sumner Maine’s Lectures on the Early History of Institutions, and John Lubbock’s The Origin of Civilisation. Out of these by far the most important was Morgan’s text, which would transform Marx’s views on the family from being the “social unit of the old tribal system” to being the “germ not only of slavery but also serfdom” (27). Morgan’s text would also strengthen the view on the state Marx had since his 1843 Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, namely, that the state is a historical (not natural) “power subjugating society, a force preventing the full emancipation of the individual” (31). The state’s nature, as Marx and Engels thought and Morgan confirmed, is “parasitic and transitory” (Ibid.). The studies of Morgan’s Ancient Society and other leading anthropologist would also be taken up by Engels who, pulling from some of Marx’s notes, would publish in 1884 The Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State, a seminal text in the classical Marxist corpus.

More unknown in Marxist scholarship are his notebooks on the Russian anthropologist Maksim Kovalevsky’s (one of his close “scientific friends”) book Communal Landownership: The Causes, Course and Consequences of its Decline. Its unstudied character is due to the fact that it had, until almost a decade ago, been only available to those who could access the B140 file of Marx’s work in the International Institute of Social History in the Netherlands. This changed with the Spanish publication in Bolivia of Karl Marx: Escritos sobre la Comunidad Ancestral (Writings on the Ancestral Community) which contained Marx’s “Cuadernos Kovalevsky” (Kovalevsky Notebooks). Although appreciative of his studies of Pre-Columbian America (Aztec and Inca empires) and India, Marx was critical of Kovalevsky’s projections of European categories to these regions, and “reproach[ed] him for homogenizing two distinct phenomena” (20). As Musto notes, “Marx was highly skeptical about the transfer of interpretive categories between completely different historical and geographical contexts” (Ibid.).

The study of Marx’s political writings has usually been limited to the 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852), the “Critique of the Gotha Program” (1875), and The Civil War in France (1871). Musto’s book, in its limited space, goes beyond these customary texts and highlights the importance of Marx’s role in the socialist movements in Germany, France, and Russia. This includes, for instance, his involvement in the French 1880 Electoral Programme of the Socialist Workers and the Workers’ Questionnaire. The program included the involvement of workers themselves, which led Marx to exclaim that this was “the first real workers’ movement in France” (46). The 101-point questionnaire contained questions about the conditions of employment and payment of workers and was aimed at providing a mass survey of the conditions of the French working class.

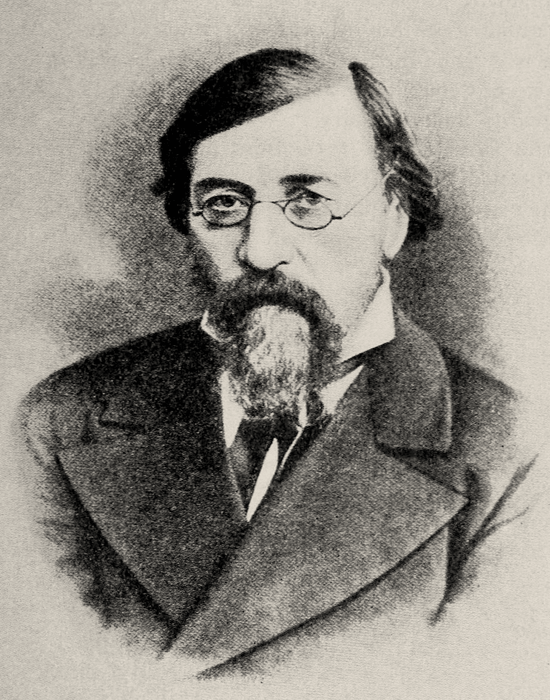

Russian socialist philosopher Nikolay Chernyshevsky (1828 – 1889)

Concerning Marx’s political writings, Musto’s text also includes Marx’s critiques of the prominent American economist Henry George; his condemnations of the Sinophobic Dennis Kearney, the leader of the Workingmen’s Party of California; his condemnations of British colonialism in India and Ireland and his praise of Irish nationalist Charles Parnell. In each case, Musto stresses the importance Marx laid on the concrete study of the unique conditions pertaining to each struggle. There was no universal formula to be applied in all places and at all times. However, out of all of his political engagements, the most important of his involvements would be in Russia, where his considerations on the revolutionary potential of the rural communes (obshchina) would have a tremendous influence on their socialist movement.

In 1869 Marx began to learn Russian “in order to study the changes taking place in the tsarist empire” (12). All throughout the 1870s he dedicated himself to studying the agrarian conditions in Russia. As Engels jokingly tells him in an 1876 letter after Marx recommended him to take down Eugene Dühring,

You can lie in a warm bed studying Russian agrarian conditions in general and ground rent in particular, without being interrupted, but I am expected to put everything else on one side immediately, to find a hard chair, to swill some cold wine, and to devote myself to going after the scalp of that dreary fellow Dühring

Out of his studies, he held the Russian socialist philosopher Nikolai Chernyshevsky 1 in highest esteem. He said he was “familiar with a major part of his writing” and considered his work as “excellent” (50). Marx even considered “’publishing something’ about Chernyshevsky’s ‘life and personality, so as to create some interest in him in the West’” (Ibid.). Concerning Chernyshevsky’s work, what influenced Marx the most was his assessment that “in some parts of the world, economic development could bypass the capitalist mode of production and the terrible social consequences it had had for the working class in Western Europe” (Ibid.).

Chernyshevsky held that

When a social phenomenon has reached a high level of development in one nation, its progression to that stage in another, more backward nation may occur rather more quickly than it did in the advanced nation (Ibid.).

For Chernyshevsky, the development of a ‘backwards’ nation did not need to pass through all the “intermediate stages” required for the advanced nation; instead, he argued “acceleration takes place thanks to the contact that the backward nation has with the advanced nation” (51). History for him was “like a grandmother, terribly fond of its smallest grandchildren. To latecomers it [gave] not the bones but the marrow” (53).

Chernyshevsky’s assessment began to open Marx to the possibility that under certain conditions, capitalism’s universalization was not necessary for a socialist society. This was an amendment, not a radical break (as certain third world Marxists and transmodernity theorists like Enrique Dussel have argued) with the traditional Marxist interpretation of the necessary role capitalism plays in creating, through its immanent contradictions, the conditions for the possibility of socialism.

In 1877 Marx wrote an unsent letter to the Russian paper Patriotic Notes replying to an article entitled “Karl Marx Before the Tribunal of Mr. Zhukovsky” written by Nikolai Mikhailovsky, a literary critic of the liberal wing of the Russian populists. In his article Mikhailovsky argued that

A Russian disciple of Marx… must reduce himself to the role of an onlooker… If he really shares Marx’s historical-philosophical views, he should be pleased to see the producers being divorced from the means of production, he should treat this divorce as the first phase of the inevitable and, in the final result, beneficial process (60)

This was not, however, a comment from left field, most Russian Marxists at the time also thought the Marxist position was that a period of capitalism was necessary for socialism to be possible in Russia. Further, Marx had also polemicized in the appendix to the first German edition of Capital against Alexander Herzen, a proponent of the view that “Russian people [were] naturally predisposed to communism” (61). His unsent letter, nonetheless, criticizes Mikhailovsky for “transforming [his] historical sketch of the genesis of capitalism in Western Europe into a historico-philosophical theory of the general course fatally imposed on all peoples, whatever the historical circumstances in which they find themselves” (64).

It is in this context that the famous 1881 letter from the Russian revolutionary Vera Zasulich must be read. In this letter she asks him the “life or death question” upon which his answer the “personal fate of [Russian] revolutionary socialists depended” (53). The question centered around whether the Russian obshchina is “capable of developing in a socialist direction” (Ibid.). On the one hand, a faction of the populists argued that the obshchina was capable of “gradually organizing its production and distribution on a collectivist basis,” and that hence, socialists “must devote all [their] strength to the liberation and development of the commune” (54). On the other hand, Zasulich mentions that those who considered themselves Marx’s “disciples par excellence” held the view that “the commune is destined to perish,” that capitalism must take root in Russia for socialism to become a possibility (54).

Marx drew up four draft replies to Zasulich, three long ones and the final short one he would send out. In his reply he repeated the sentiment he had expressed in his unpublished reply of Mikhailovsky’s article, namely, that he had “expressly restricted… the historical inevitability’ of the passage from feudalism to capitalism to ‘the countries of Western Europe’” (65). If capitalism took root in Russia, “it would not be because of some historical predestination” (66). It was then, he argued, completely possible for Russia – through the obshchina – to avoid the fate history afforded Western Europe. If the obshchina, through Russia’s link to the world market – “appropriate[d] the positive results of [the capitalist] mode of production, it is thus in a position to develop and transform the still archaic form of its rural commune, instead of destroying it” (67).

In essence, if the internal and external contradictions of the obshchina could be sublated through its incorporation of the advanced productive forces that had already developed in Western European capitalism, then the obshchina could develop a socialism grounded on its appropriation of productive forces in a manner not antagonistic to its communistic social relations. Marx would then, in the spirit of Chernyshevsky, side with Zasulich on the revolutionary potential of the obshchina and argue for the possibility of Russia not only skipping stages but incorporating the productive fruits of Western European capitalism while rejecting its evils. This sentiment is repeated in his and Engels’ preface to the second Russian edition of the Manifesto of the Communist Party, which would be published on its own in the Russian populist magazine People’s Will.

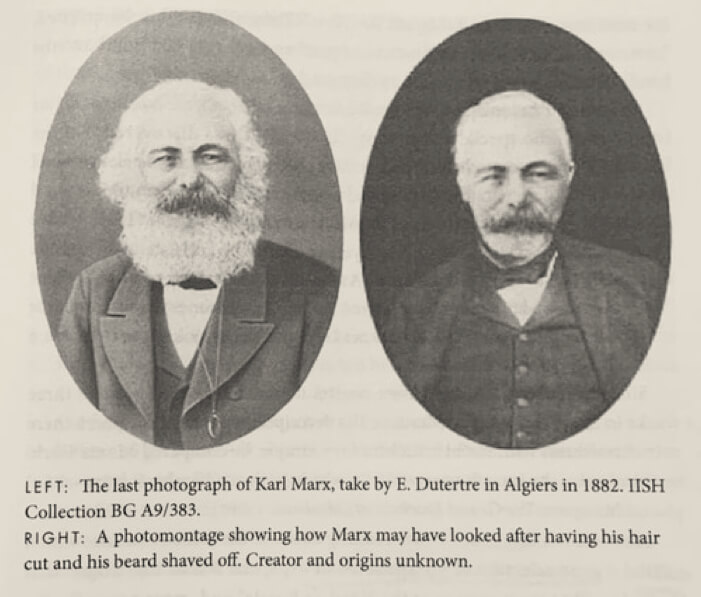

Musto’s text also provides an exceptional picture of the largely unexamined 72 days Marx spent in Algiers, “the only time in his life that he spent outside of Europe” (104). This trip came at the recommendation of his doctor, who was constantly moving him around in search of climates more favorable to his health condition. Eleanor recalled that Marx warmed up to the idea of the trip because he thought the favorable climate could create the conditions to restore his health and finish Capital. She said that “if he had been more egoistic, he would have simply allowed things to take their course. But for him one thing stood above all else: devotion to the cause” (103).

The Algerian weather was not as expected, and his condition would not improve to a shape where he could return to his work. Nonetheless, the letters from his time in Algiers provide interesting comments about the social relations he experienced. For instance, in a letter to Engels he mentions the haughtiness with which the “European colonist dwells among the ‘lesser breeds,’ either as a settler or simply on business, he generally regards himself as even more inviolable than handsome William I” (109). After having experienced “a group of Arabs playing cards, ‘some of them dressed pretentiously, even richly” and others poorly, he commented in a letter to his daughter Laura that “for a ‘true Muslim’… such accidents, good or bad luck, do not distinguish Mahomet’s children,” the general atmosphere between the Muslims was of “absolute equality in their social intercourse” (108-9).

Marx also commented on the brutalities of the French authorities and on certain Arab customs, including in a letter to Laura an amusing story about a philosopher and a fisherman which “greatly appealed to his practical side” (110). His letters from Algiers add to the plethora of other evidence against the thesis, stemming from pseudo-radical western bourgeois academia, that Marx was a sympathizer of European colonialism.

Shortly after his return from his trip Marx’s health continued to deteriorate. The combination of his bed-ridden state and Jennychen’s death made his last weeks agonizing. The melancholic character of this time is captured in the last writing Marx ever did, a letter to Dr. Williamson saying “I find some relief in a grim headache. Physical pain is the only ‘stunner’ of mental pain” (123). A couple months after writing this, on March 14th, 1883, Marx would pass away. Recounting the distress of the experience of finding his life-long friend and comrade dead, Engels wrote in a letter to Friedrich Sorge an Epicurean dictum Marx often repeated – “death is not a misfortune for the one that dies but for the one that survives” (124).

In sum, it would be impossible to do justice, in such limited space, to such a magnificent work of Marxist scholarship. However, I hope I have been able to clarify some of the reasons why Musto is right to lay such seminal importance on this last, often overlooked, period of Marx’s life and work.

Footnotes

- Chernyshevsky was the author of What is to be Done (1863), a title V. I. Lenin would take up again in 1902.

- Marcello Musto, The Last Years of Karl Marx: An Intellectual Biography. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA, 2020. 194 pp., $22. ISBN 9781503612525

Republished with permission from Midwestern Marx. Photo: Karl-Marx-Statue, Trier by Max Gerlach via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0).