This article is based on a speech by Ford to the 62nd Annual Convention of the Arkansas State Conference of the NAACP, in Little Rock.

For much of the past month, African Americans commemorated the Little Rock Nine’s integration of Central High School, September 25, 1957. For the most part, celebrations highlighted the teenagers’ courage in the face of state-instigated mob violence, and the steadfastness of their parents and NAACP organizers.

This is an heroic story, glorious on its face, and true. Yet the real significance of the events of 50 years ago extends far beyond issues of school desegregation – a problematic legacy in light of what has since transpired.

Rather, the Little Rock Nine and their adult mentors – without knowing it, and some possibly still unaware of the full impact of their actions – set in motion a chain of events that would fundamentally alter the political relationship between Blacks and the white power structure in the United States.

Arkansas National Guard at Little Rock Central High School, Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site, 1957

Were it not for the Little Rock Nine, the whirlwind advances of the Sixties, resulting in the death of legal Jim Crow in historical lightning speed, might have been a much longer, drawn out battle. Their victory in a token effort to integrate a high school in the capitol city of Arkansas did not lead to a national continuum of ever-expanding classroom desegregation – or even to completion of an integrated high school experience for all of the students, themselves.

Instead, the Little Rock Nine focused national and world attention on the real nature of white mob violence in the United States, for the first time through the young medium of television. A segregationist president was compelled against every political instinct to bring the full powers of the federal government, including military force, to bear on the side of Blacks for the first time since the death of Reconstruction. And the stage was set for an era in which the two political parties would actively vie for the Black vote, one of which would closely collaborate with Black leadership in an attempt to reinvent America.

A Shock to the Senses

The broad outlines of the September, 1957, chronology are well-known.A local school board-sanctioned plan to trickle nine Blacks into the 2000-student body of Central High School prompted an enraged Gov. Orval Faubus to deploy Arkansas National Guardsmen to bar the schoolhouse door to the Black students, on September 4. A federal judge ordered the Guard removed, and that integration move forward under local police protection, September 20.

Meanwhile, racists from throughout the region had worked themselves into a frenzy. On September 23, a 1,000-strong mob threatened to storm the school building, forcing police to evacuate the Little Rock Nine. The city’s mayor asks Washington to send in federal troops to restore order. A profoundly reluctant President Dwight Eisenhower takes the Arkansas National Guard away from Governor Faubus, by federalizing it, and on September 25 sends in 1,000paratroopers to escort the nine Black students into Central High, while a huge gathering of the white racist citizenry behave like obscenity screaming savages for all the world to see and hear.

A first-class civil rights drama, to be sure – but the fallout was history-bending. Never before had Americans viewed from their living rooms the raw face of white racist mob blood lust. Although many had read about lynchings, few knew that these macabre events were often attended by thousands,with whole families assembling in a picnic atmosphere. Besides, that was all in the past, and most Americans – and foreigners – had imbibed a diet of Gone with the Wind and Cabin in the Sky movie fictions of benign southern racial relationships.

The gruesome 1955 murder of Black teenager Emmett Till, in Mississippi, had received national and world attention, as did the Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott, the same year. However, the Till lynching was the work of furtive night killers, and the boycott of Montgomery buses was not accompanied by a mass white mob response. White southern politicians regularly warned of an apocalypse should Blacks continue to press for enforcement of the 1954 Brown school desegregation decision, but thanks to the executive and judicial branches’ insistence on giving whites all the time in the world to comply, Armageddon had not occurred.

Suddenly, there it was: the coiled white mob, including large numbers of women and children, their faces contorted in hate, spitting and blaspheming, grotesque and murderous animals bent on tearing apart children. This was truly the Ugly American, caught on video in his and her native habitat. (“The niggers got in! They tricked us! The niggers got in!” “Come on, let’s go in the school and drag them out!”)

Six years before television would record Birmingham’s police dogs and fire hoses – a horror of state violence, rather than white mob depredations – the 1957 Little Rock display of mass white southern inhumanity changed the image of the United States, irrevocably.

The Segregationist Savior

A rapidly decolonizing world was watching, the Soviets were pointing and chuckling, and the former general-of-all-generals in the White House had been waylaid by a new history in the making, one that he could not avoid. Dwight Eisenhower is called “a man of his times” by his apologists – meaning, he was a segregationist. As Supreme Commander in World War Two, Eisenhower opposed integration of the Armed Forces, on the grounds that it would damage white troop morale and “harm the Negro” by forcing him to compete with whites – arguments near-identical to those put forward by polite segregationists in civilian life. Ike put it this way:

“In general, the Negro is less well educated … and if you make a complete amalgamation, what you are going to have is in every company the Negro is going to be relegated to the minor jobs, and he is never going to get his promotion to such grades as technical sergeant, master sergeant, and soon, because the competition is too tough. If, on the other hand, he is in smaller units of his own, he can go up to that rate, and I believe he is entitled to the chance to show his own wares…I believe that the human race may finally grow up to the point where it [race relations] will not be a problem. It [the race problem] will disappear through education, through mutual respect, and so on. But I do believe that if we attempt merely by passing a lot of laws to force someone to like someone else, we are just going to get into trouble. On the other hand, I do not by any means hold out for this extreme segregation as I said when I first joined the Army 38 years ago.”

Eisenhower got help in his victorious bid for the presidency, in 1952, from Harlem Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, who was sick and tired of the Dixie Democrats that dominated the Party at the congressional level. Possibly due to Powell’s influence, Eisenhower stated, in a March, 1953 press conference:

“I will say this – I repeat it, I have said it again and again: whenever Federal funds are expended for anything, I do not see how any American can justify – legally, or logically, or morally – a discrimination in the expenditure of those funds as among our citizens. All are taxed to provide these funds. If there is any benefit to be derived from them, I think they must all share, regardless of such inconsequential factors as race and religion.”

Note, however, that this bland statement says nothing about federal intervention to enforce his personal opinion, and is totally compatible with the “separate but equal” doctrine. As Morris J. MacGregor Jr. wrote in his authoritative Integration of the Armed Forces, 1940-1965, Eisenhower contended “it was not in the scope of the President’s authority “to intervene in matters which are of local or state-wide concern and within the jurisdiction of local legislation and determination.”

In other words, Ike believed in “state’s rights,” just like the Dixiecrats.

The tenacity of the Little Rock Nine, their parents, and the NAACP forced Eisenhower’s hand. More accurately, the whites that Eisenhower had always feared upsetting compelled him to react, in the name of law and order, the powers of the presidency, and the global image of the United States. He sent in the troops, and nothing would ever be the same again.

Democrats Slow to Catch Up

The racist rantings of Dixiecrats, who had bolted the Democratic Party in 1948 in reaction to mild integrationist language in the Party platform, plus Adam Clayton Powell’s sympathy for Eisenhower’s presidency, garnered Ike 39 percent of the Black vote in 1956 – higher than any Republican presidential candidate since Franklin Roosevelt sewed up the Black vote in 1936. The Democrats were busy trying to patch up relations with their Dixiecrat brethren, in the early and mid-Fifties, further alienating Black voters.

September 4, 1957: Arkansas National Guard soldiers were ordered to prevent the Little Rock Nine from entering Central High. Reportedly, there was a crowd across the street chanting, “Two, four, six, eight, we don’t want to integrate.”

Eisenhower’s decisive action in 1957 Little Rock made him a hero in Black America. Not in most people’s living memory had federal troops been deployed on the “right” side of the race divide – but Ike did it. If he could build for Republicans on his 1956 Black 39 percent share, the Democrats would be in crisis in 1960. Little Rock created a huge bump in Ike’s Black popularity, but the Democrats were slow to understand the implications.

Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson (TX) declared, “There should be no troops from either side patrolling our school campuses anywhere.”

Adlai Stevenson, the 1952 and 1956 losing Democratic presidential candidate, speaking at the beginning of the Little Rock crisis, but before Eisenhower sent in the troops, said, “I don’t suppose the president has much that he can do” – that is, Stevenson could not contemplate enforcing the law with federal forces.

John Kennedy, a clear candidate for the next election cycle, said that “though there may be disagreement over the president’s leadership on this issue, there is no denying that he alone had the ultimate responsibility for deciding what steps are necessary to see that the law is faith fully executed” – faint praise, indeed.

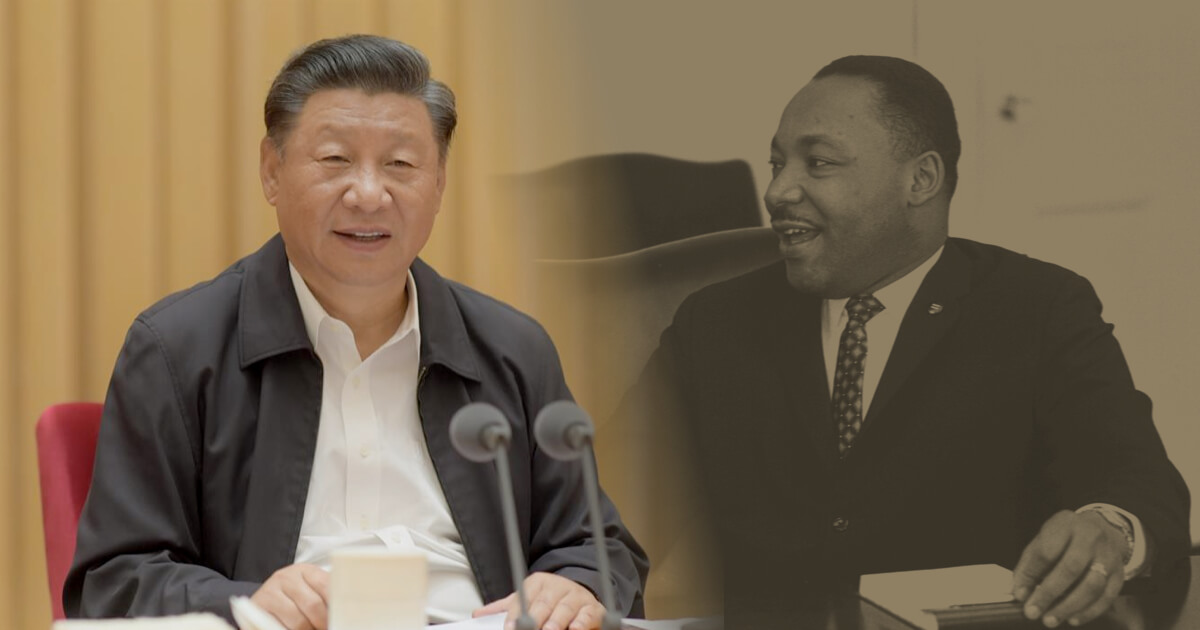

As the next election drew nearer – and as polls showed Eisenhower’s soaring approval ratings among African Americans – it finally dawned on Democrats that Vice-President Richard Nixon might inherit Ike’s Black support. Late in the game, in the midst of the 1960 campaign, Kennedy trumped the Republicans with a call to Coretta Scott King, expressing sympathy for her husband’s having been imprisoned in Reidsville, Georgia. Brother Bobby was dispatched to urge Georgia authorities to release Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on bail. “I’m sure that the senator did it because of his real concern and his humanitarian bent,” said King – and a new white political hero was born.

All three of the Nixon-Kennedy televised debates dealt with questions of civil rights, as they jockeyed for Black support. The process of disentanglement from the Dixiecrats had begun – an unlikely occurrence had Eisenhower not been forced to become a reluctant Black savior by the sheer courage of the Little Rock Nine, thus endangering the Democrats’ lock on Black voters.

Nixon lost the election by a hair. “If the Negro voters of America hadn’t shifted last Tuesday to John Kennedy, Vice-President Nixon would now be holding press conferences as President-elect,” said The New Republic. “Kennedy’s victory with the Negroes was nothing short of triumphant,” wrote Time magazine. Eisenhower blamed Nixon’s defeat on his failure to attract enough Black votes.

The Legacy

The Black-Democratic love affair was rekindled, but at a price for white Democrats. Because of Eisenhower’s actions in Little Rock, and Kennedy’s efforts to one-up him by embracing Dr. King (no matter how cynically), African Americans grew to realize their centrality in national elections, as did their white suitors. For Kennedy, and later Johnson, there was no going back; the Dixiecrat ties were doomed.

Soon the “Big Four” of civil rights – the Southern Christian Leadership Council’s Martin Luther King Jr., Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, Whitney Young of the Urban League, and James Farmer of the Congress of Racial Equality – and other Black luminaries would feel confident in demanding meetings at the White House, a venue every previous generation of African Americans were made to feel privileged and lucky to set foot in. They arrived with agendas, rather than an “I’m so glad to be here” attitude. They competed with each other to present coherent programs that would finally be considered as potential public policy. They, and the movements they represented, shaped a Second Reconstruction, albeit brief and inadequate.

If the Little Rock Nine had faltered, history would have unfolded quite differently. Their greatest legacy is having boxed in a segregationist president, forcing him to do the right thing, and provoked, by their heroism, white mobs to show their asses to the candid cameras of television, thus teaching the planet the real character of U.S. white society in 1957, a spectacle that previously indifferent whites would seek to live down for many years.

From that moment on, the Black American world changed.

Republished with permission from Black Agenda Report. Photos are in the public domain.