In the US we have the popular idea that science is apolitical. And this may be true when it comes to results in a lab, but the conditions in which this knowledge is created certainly are political. Decisions over what knowledge is important, what projects receive funding, how studies are constructed, and, as we will see, who gets tested on are deeply influenced by political and economic considerations. Throughout much of American history many of these considerations were of the racist, imperialist, and capitalist variety. In this essay, I will explore the histories of the Tuskegee and Guatemalan Syphilis Studies to illustrate this history.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study was a long-term observational study meant to track the affects of latent syphilis in black men. However, before we can get to the study itself, we need to understand a few basic things about Syphilis and the state of science at the time. Syphilis is caused by a bacterium known as Treponema pallidum and can be acquired through sexual activity or congenitally, through an infected mother. Once infected, the disease appears in three stages. The first stage of sexually transmitted Syphilis is characterized by painless chancre sores on the point of entry followed by flu-like symptoms. If left untreated the disease enters a prolonged latent stage until it reemerges with an assortment of symptoms such as skin sores, bone decay and cardiovascular damage. The third and final stage can erupt years later causing serious neurological damage leading to blindness, insanity, paralysis, and death. 1

In the late 1920s, US medical science was heavily influenced by eugenicist and Social-Darwinian racial theories, with Syphilis being no exception. This led many doctors of the time- particularly those at the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS)- to believe Syphilis followed a different course in black people than in whites, arguing black people were more likely to suffer from cardio-syphilis while white people were more likely to have neuro-syphilis. 2 Many of these scientists also believed black people were a uniquely “Syphilis soaked race”. According to logic twisted by white supremacy, black people, having lost the enlightened influence of their white masters, had reverted to barbaric tendencies characterized by sexual profligacy and immorality making them more susceptible to Syphilis. Further, they argued black people were suspicious of western medicine, which was somewhat true. 3 However, rather than being due to an irrational fear of treatment borne out of ignorance as the PHS doctors believed, this was more a natural reaction to the already well-established proclivity of white scientists to experiment on black bodies. 4 But it seems the rule among these doctors was that any evidence to the contrary, such as the fact that most Syphilis cases were transmitted congenitally not sexually 5 or that black people often did seek out treatment when it was available 6, were dismissed. With this, many doctors concluded black people were a doomed race and attempts to treat them would make little difference, leading PHS Physician Thomas W. Murrel to write:

“So the scourge sweeps among them. Those that are treated are only half cured, and the effort to assimilate a complex civilization driving their diseased minds until the results are criminal records. Perhaps here, in conjunction with tuberculosis, will be the end of the negro problem. Disease will accomplish what man cannot do.” 7

Which brings us to Macon County, Alabama. Home to the famous Tuskegee Institute. Macon County’s population was majority black with at least half of these black people living in crushing poverty. 8 Many black people in Macon County were tenant farmers or sharecroppers which were special forms of debt-peonage. Under these arrangements, the farmers did not own the land they worked on, the house they lived in, or the tools they used. These were loaned to the farmers at usurious rates by their mainly white landlords. Often these farmers ended up trapped in debt effectively chained to the land like Feudal serfs. 9 As far as medical care went, there were 16 doctors in Macon County, but fifteen of them were white, overpriced, and only accepted cash which poor farmers rarely had. There was only one overworked black doctor who would accept other forms of payment such as livestock. Additionally, the medical facility at Tuskegee Institute would treat some cases, but only a fraction of what was needed as the facility’s purpose was to treat students and faculty of Tuskegee. 10 As it was, medical treatment in Macon County was virtually non-existent for black people. This vulnerability made the black people of Macon County ideal subjects for the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.

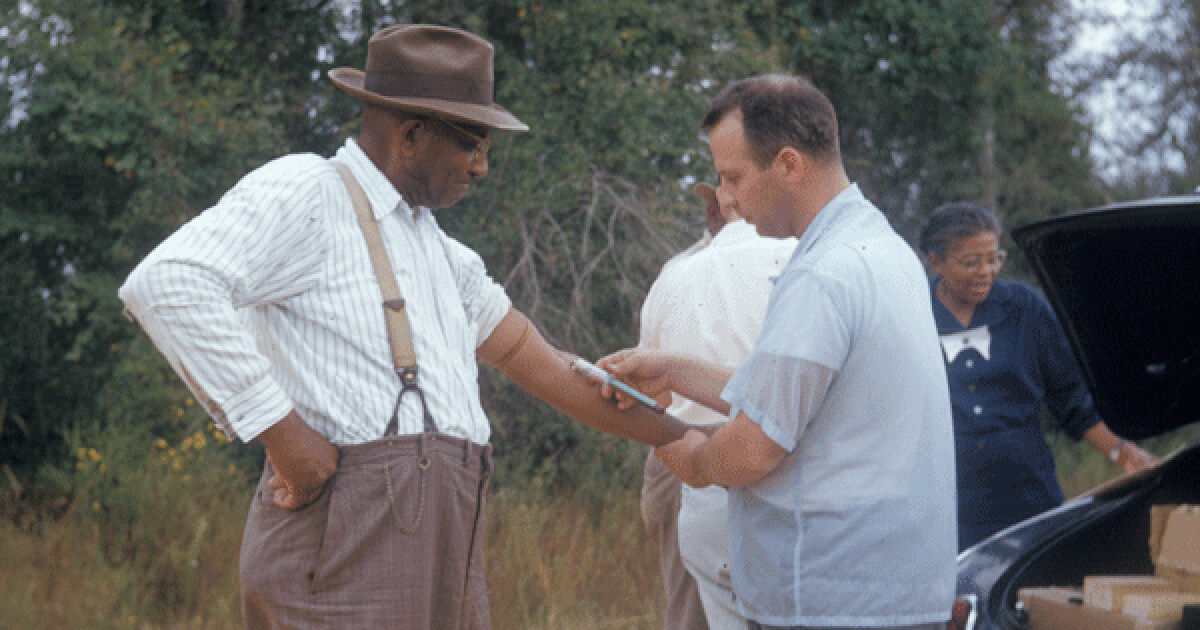

The beginnings of the study were innocent enough. In 1929, the Julius Rosenwald Fund approached the PHS about beginning a series of testing and treatment facilities for Syphilis in the south. After a successful campaign in Bolivar County, Mississippi, the Rosenwald Fund provided the PHS with $50,000 to begin similar testing and treatment programs in the rural south. The PHS chose five counties in the south to begin these programs with one of them being Macon County, Alabama. 11 Testing began in 1930, but quickly hit some major issues. Faced with a population unable to travel great distances to reach testing sites and suspicious of white doctors, the PHS began employing black healthcare workers to travel to these communities to carry out testing. Additionally, researchers did not tell patients they were being tested for Syphilis. Instead, they called it “bad blood”- a catch-all term for various diseases of the time. 12 Using the standard Wasserman test, the study found an average infection rate of 25% across the five counties, with Macon County having the highest of 36%. Further, the study found that mass treatment among these communities was feasible, but as they prepared to begin treatment, the Great Depression began. 13

Exemplifying the pitfalls of making your medical research contingent on private generosity, the Great Depression drained the Rosenwald Fund and, with it, the possibility of continuing treatment. However, Dr. Taliaferro Clark, head of the PHS Venereal Disease Division, saw an opportunity in Macon County. Noting the high rate of Syphilis and continuing to believe black people would reject medical care, Clark wanted to continue the study without treatment to observe the long-term course of the disease in black men. Clark hoped to test if the disease did manifest differently in black men than in whites and explore the possibility that mass treatment among black people was unnecessary. 14 Clark, in conjunction with fellow PHS Dr. Raymond Vonderlehr, decided to carry out a six month observational study of black men with Syphilis and managed to milk another $10,000 out of the Rosenwald Fund on the condition that treatment be given after the six month observational period. 15

Having learned from previous efforts, the PHS enlisted the help of black health professionals such as nurse Eunice Rivers and Dr. H. L. Harris Jr. to ameliorate fears black subjects may have. They also enlisted the help of the famous Tuskegee Institute. Founded by Booker T. Washington in 1898, it was one of the most prestigious black colleges in the United States. Eager to gain funding and participate in a national medical study, the administration jumped at the opportunity, offering the services of the university’s medical facilities headed by Eugene H. Dibble. 16

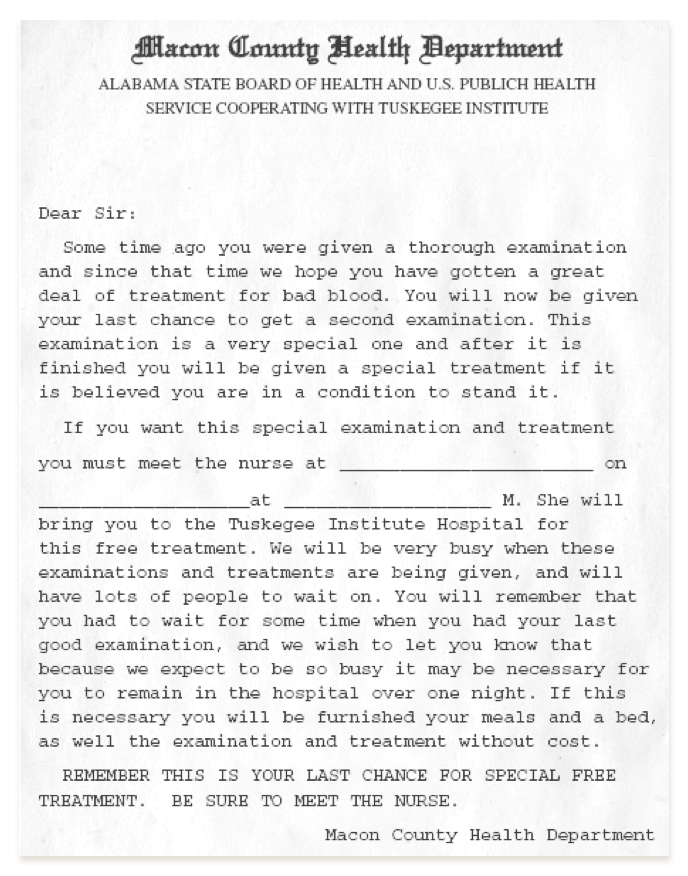

Continuing to refer to it as “Bad Blood”, the PHS induced people to join the study with promises of treatment. To determine if a person was right for the study, the subject was given two Wasserman tests, a full physical examination, and medical history interviews. Finally, the men were given very painful spinal taps under the guise of “special free treatment” to determine if they had neurosyphilis. 17 To keep men who insisted on treatment interested, Dr. Vonderlehr often gave out useless mercury ointments or insufficient doses of neoarsphenamine as fake treatments. 18 Men chosen for the project were over 25 years old, had a history of limited or no treatment, and had had Syphilis for more than 5 years. Ultimately, the study recruited 439 men with Syphilis and a control group of 185 men without Syphilis. 19 And despite the fact that black people proved not only receptive to treatment, but often insisted on it, disproving their assumptions about black men’s attitudes to medicine, the doctors decided to continue the study in 1933 once the Rosenwald funding ran out and treatment completely ended. 20

After the group was chosen, the study was mainly confined to frequent visits by nurse Rivers to inquire into how the men’s condition and occasional visits to the clinic to have blood drawn and more spinal taps conducted. However, the PHS also sought to prevent the men from seeking treatment from other sources. For instance, Dr. Vonderlehr met with groups of black doctors in the area asking them to not treat the men. In 1941, the PHS went as far as to provide the draft board with a list of names of men who were to be excluded from Syphilis treatment if they were drafted for World War II. 22 Most damningly, the researchers continued this after penicillin was discovered to be an effective cure for Syphilis and had been successfully used in treatment campaigns across the country. 23

Letter to the participants. Reproduced from materials at the University of Illinois’s Poynter Center for the Study of Ethics and American Institutions

21 The rest of the PHS researchers’ activity in the interim were geared towards securing bodies for autopsy once the men died. The doctors needed the autopsies to analyze the impact Syphilis had on the men’s bodies, but rural black populations were strongly opposed to this and if the men died at home instead of the Tuskegee hospital, the doctors may not get the body. Thus, the doctors used nurse Rivers to track the men’s movement to ensure the men died at the hospital or persuade their families to assent to autopsy by referring to it as an “operation”. For extra incentive, the doctors also offered to cover the burial costs of the men, which was a major inducement as a dignified burial would have been a major expense to these families. 24 Importantly, the doctors kept their intentions under wraps, with Dr. Vonderlehr noting, “Naturally, it is not my intention to let it be generally known that the main object of the present activities is the bringing of the men to necropsy.” 25

While it may not have been a major impetus to start the project, a profit motive certainly provided justification for its continuation. Perhaps the only actual contribution the study made to science was to serve as a source of Syphilis infected blood. Tests available at the time were notoriously inaccurate, but, because scientists would not know how to culture Syphilis independently in a lab until the 1950s, they required a constant supply of Syphilis infected blood to develop new tests. As part of a broader group of studies known as the Cooperative Clinical Group, samples obtained from the men through continued blood drawing and spinal taps, were supplied to the PHS to develop more sensitive tests. Using these samples, the PHS did manage to develop two more accurate tests, which the PHS then marketed globally making a nice profit. 26

Despite many PHS employees raising ethical concerns over the years, the project was continued until 1972, when a former PHS employee informed a journalist friend who broke the story for the Associated Press. As public outcry grew, the study was swiftly ended in March of 1973. After this, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) commissioned an investigation which issued a milquetoast condemnation, which many members of the investigation claimed had been watered down against their will. 27 In 1973, Macon County lawyer, Fred Gray, filed a class-action lawsuit on behalf of the participants of the Tuskegee Study. They eventually settled out of court in 1974 for a fraction of what they had sued for. Each living subject in the experimental group were given $37,500 each, with $15,000 for their heirs, and nearly $1 million in legal fees to Fred Gray which was to be taken from the men’s payments. Those living members of the control group were given less. 28

As for the scientific value of the study, the results were ultimately worthless. During the study 12 men in the control group contracted Syphilis and were simply switched over to the experimental group.[29] Additionally, despite the best efforts of researchers, many of the men did receive some treatment over the years, compromising their untreated status. 30 Ultimately, the cost for this worthless information was at least 16 men who died directly from Syphilis, although the number could possibly be much greater. 31 And, since the men were not notified of their infection, they likely infected others. 32

The legacy of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study is far reaching. It is still often cited as a reason for black Americans’ distrust of the medical profession. And, while the Tuskegee study is well known among black people, it is far from the singular reason for black distrust in modern medicine. It was part of a broader and longer legacy of testing on minorities in the United States and people in the global south. However, one of the most famous accusations against the Tuskegee Study- that doctors deliberately infected black men- is a misconception. 33 The PHS did not purposely infect people at Tuskegee; they did that in Guatemala.

Following World War II, it was known that Penicillin could be used as an effective cure for Syphilis and several other diseases, but researchers also wanted to know if penicillin could be used as a prophylaxis against venereal disease. During the war, the military had distributed prophylaxis ointments, but they were painful when used, incentivizing the government to find less painful ways of guarding against venereal disease. 34 Previously, in 1944, the PHS had done experiments on prophylaxis against gonorrhea at the Terre Haute Federal Penitentiary in the U.S. “Volunteers” were injected with gonorrhea, but the project was abandoned after the doctors had trouble getting subjects to exhibit symptoms. 35 After this failure, the PHS set its sites on the global south to answer this question.

In 1946 the PHS dispatched Dr. Julius Butler- who had been involved in the Terre Haute experiment and would go on to be involved in the Tuskegee study- to Guatemala to test the possibilities of using penicillin to prevent contraction of venereal disease. At the time, much of Guatemala was owned by the United Fruit Company putting it firmly in the control of the U.S. empire. Additionally, the little public health infrastructure that existed was in large part controlled by the U.S. and the leading venereal disease public health official was the PHS trained Dr. Juan Funes. 36 The PHS again enlisted the most vulnerable populations. Throughout the study, subjects included, prisoners, orphans, patients in Guatemala’s only mental asylum, and soldiers stationed in the capital.

They began with inmates at Guatemala City’s Central Penitentiary. At the time, Guatemala had legal prostitution and prostitutes could visit incarcerated men. Using this, the PHS payed prostitutes who had tested positive for Syphilis or Gonorrhea to visit the men in prison. If a prostitute did not have Syphilis, the researchers would place an inoculum on the woman’s cervix, hoping this would transmit the disease. The men were given tests before and after the visits from the prostitutes and were divided into groups to be given various chemical and biological prophylaxis and the results observed. However, unlike the Tuskegee study, subjects were supposed to be given adequate penicillin to cure them. 37 The researchers quickly ran into difficulties, as prostitutes and prisoners proved much harder to control than they had expected, and not enough men were contracting the disease. Also, there was still the problem with the sensitivity of available tests, which frequently gave off false positives and negatives. 38 The researchers quickly abandoned the prison experiment and turned to the national orphanage. They conducted blood tests on 439 children and observed the results, hoping to develop more reliable testing methods. 39

Finally, they turned to the nation’s only mental asylum. Here, because they were not able to introduce prostitutes, the PHS doctors directly inoculated patients by introducing Syphilitic material directly to the genitalia, telling asylum officials this was just another form of drug. 40 Subjects were then given various forms of prophylaxis, and, if the subject became infected, they were supposed to be cured. The PHS combined both methods of infection on soldiers living in Guatemala City’s barracks, using both direct inoculation and prostitutes and, again, providing various forms of prophylaxis to be tested. 41 According to the U.S. Bioethical Issues Commission, in total, 1308 subjects were inoculated with some form of STD, 678 people received treatment, and over 5,000 were included in diagnostic studies. The Guatemalan government puts the total inoculated at 2,082. During the course of the study, 83 subjects died, though it is not clear whether or not these were as a result of inoculations. 42

So, what can we learn from these studies? The most obvious lesson is the role racist and eugenicist theories have played in the history of American medicine. It is important to understand these are not aberrations. Testing on vulnerable people, particularly slaves, has been a common feature of U.S. medicine over the past two centuries- see Marion Sims and the development of modern gynecology. Further, these studies were supported at the highest levels of powerful government institutions, showing how access to political and economic power can shape scientific research. Throughout both these studies, the PHS used both to induce cooperation from smaller institutions such as the Tuskegee Institute and Guatemalan public health officials. Often these institutions leveraged their collaboration in the studies to gain supplies for treatment of people who would not have received treatment otherwise, perfectly illustrating the problems of power imbalances in research. Finally, in the age of Covid, it shows us how unethical medical researchers can prey on the most vulnerable populations, particularly those in the clutches of U.S. imperialism.

Footnotes

- Washington, Harriet. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present, 138. New York City, NY: Broadway Books, 2008.

- Blake, Lindsay. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study: Medical Research Versus Human Rights. Augusta.OpenRepository.com

- Brandt, Allan M. 1978. “Racism and research: The case of the Tuskegee Syphilis study.” The Hastings Center Report 8(6): 21-29.

- Washington, Harriet. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. New York City, NY: Broadway Books, 2008

- Washington, Harriet. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. p139. New York City, NY: Broadway Books, 2008

- Brandt, Allan M. 1978. “Racism and research: The case of the Tuskegee Syphilis study.” The Hastings Center Report 8(6): 21-29.

- Brandt, Allan M. 1978. “Racism and research: The case of the Tuskegee Syphilis study.” The Hastings Center Report 8(6): 21-29.

- Washington, Harriet. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present, 137. New York City, NY: Broadway Books, 2008

- “Foundations of Oppression: The Antebellum South Appalachian Class Dynamic.” libcom.org. Accessed November 10, 2020.

- Washington, Harriet. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present, 137. New York City, NY: Broadway Books, 2008

- Blake, Lindsay. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study: Medical Research Versus Human Rights. Augusta.OpenRepository.com

- Blake, Lindsay. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study: Medical Research Versus Human Rights. Augusta.OpenRepository.com

- Blake, Lindsay. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study: Medical Research Versus Human Rights. Augusta.OpenRepository.com

- Brandt, Allan M. 1978. “Racism and research: The case of the Tuskegee Syphilis study.” The Hastings Center Report 8(6): 21-29.

- Blake, Lindsay. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study: Medical Research Versus Human Rights. Augusta.OpenRepository.com

- Blake, Lindsay. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study: Medical Research Versus Human Rights. Augusta.OpenRepository.com

- Brandt, Allan M. 1978. “Racism and research: The case of the Tuskegee Syphilis study.” The Hastings Center Report 8(6): 21-29.

- Brandt, Allan M. 1978. “Racism and research: The case of the Tuskegee Syphilis study.” The Hastings Center Report 8(6): 21-29.

- Reverby, S.M. Ethical Failures and History Lessons: The U.S. Public Health Service Research Studies in Tuskegee and Guatemala. Public Health Rev 34, 13 (2012). DOI.org

- Brandt, Allan M. 1978. “Racism and research: The case of the Tuskegee Syphilis study.” The Hastings Center Report 8(6): 21-29.

- “The Experiment.” Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. Accessed November 11, 2020. tuskegeesyphilisexperimentt.weebly.com

- “The Experiment.” Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. Accessed November 11, 2020. tuskegeesyphilisexperimentt.weebly.com

- Washington, Harriet. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present, 144-145. New York City, NY: Broadway Books, 2008

- Washington, Harriet. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present, 142-143. New York City, NY: Broadway Books, 2008

- Brandt, Allan M. 1978. “Racism and research: The case of the Tuskegee Syphilis study.” The Hastings Center Report 8(6): 21-29.

- Washington, Harriet. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present, . New York City, NY: Broadway Books, 2008

- Roy B. The Tuskegee syphilis experiment: medical ethics, constitutionalism, and property in the body. Harv J Minor Public Health. 1995 Fall-Winter;1(1):11-5. PMID: 11656513.

- Blake, Lindsay. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study: Medical Research Versus Human Rights. Augusta.OpenRepository.com

- Reverby, S.M. Ethical Failures and History Lessons: The U.S. Public Health Service Research Studies in Tuskegee and Guatemala. Public Health Rev 34, 13 (2012). DOI.org

- Reverby, S.M. Ethical Failures and History Lessons: The U.S. Public Health Service Research Studies in Tuskegee and Guatemala. Public Health Rev 34, 13 (2012). DOI.org

- Reverby, S.M. Ethical Failures and History Lessons: The U.S. Public Health Service Research Studies in Tuskegee and Guatemala. Public Health Rev 34, 13 (2012). DOI.org

- Reverby, S.M. Ethical Failures and History Lessons: The U.S. Public Health Service Research Studies in Tuskegee and Guatemala. Public Health Rev 34, 13 (2012). DOI.org

- REVERBY, S.M. (2001), More than Fact and Fiction: Cultural Memory and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Hastings Center Report, 31: 22-28. DOI.org

- Reverby, S. (2011). “Normal Exposure” and Inoculation Syphilis: A PHS “Tuskegee” Doctor in Guatemala, 1946–1948. Journal of Policy History, 23(1), 6-28. doi:10.1017/S0898030610000291

- Reverby, S.M. Ethical Failures and History Lessons: The U.S. Public Health Service Research Studies in Tuskegee and Guatemala. Public Health Rev 34, 13 (2012). DOI.org

- Reverby, S.M. Ethical Failures and History Lessons: The U.S. Public Health Service Research Studies in Tuskegee and Guatemala. Public Health Rev 34, 13 (2012). DOI.org

- Reverby, S. (2011). “Normal Exposure” and Inoculation Syphilis: A PHS “Tuskegee” Doctor in Guatemala, 1946–1948. Journal of Policy History, 23(1), 6-28. doi:10.1017/S0898030610000291

- Reverby, S. (2011). “Normal Exposure” and Inoculation Syphilis: A PHS “Tuskegee” Doctor in Guatemala, 1946–1948. Journal of Policy History, 23(1), 6-28. doi:10.1017/S0898030610000291

- Reverby, S. (2011). “Normal Exposure” and Inoculation Syphilis: A PHS “Tuskegee” Doctor in Guatemala, 1946–1948. Journal of Policy History, 23(1), 6-28. doi:10.1017/S0898030610000291

- Reverby, S. (2011). “Normal Exposure” and Inoculation Syphilis: A PHS “Tuskegee” Doctor in Guatemala, 1946–1948. Journal of Policy History, 23(1), 6-28. doi:10.1017/S0898030610000291

- Reverby, S. (2011). “Normal Exposure” and Inoculation Syphilis: A PHS “Tuskegee” Doctor in Guatemala, 1946–1948. Journal of Policy History, 23(1), 6-28. doi:10.1017/S0898030610000291

- Reverby, S.M. Ethical Failures and History Lessons: The U.S. Public Health Service Research Studies in Tuskegee and Guatemala. Public Health Rev 34, 13 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03391665

Re-published with permission from Midwestern Marx