The term “Radlib,” or Radical Liberal, is thrown around on the internet within leftist/Marxist circles quite often. The word is usually an accusatory term. Roughly speaking, the term is used to accuse someone of being essentially a liberal with the trappings of radicalism. Among Marxists the term is used to accuse someone professing to be a Marxist, but largely retains the mentality of liberalism. The meaning of the term is highly elastic and context-sensitive, sometimes even to a fault. In this essay, I’ll attempt to explore the phenomenon of radical liberalism from a Marxist perspective. I think the most useful starting point is to explain the distinction between Utopian Socialism and Scientific Socialism.

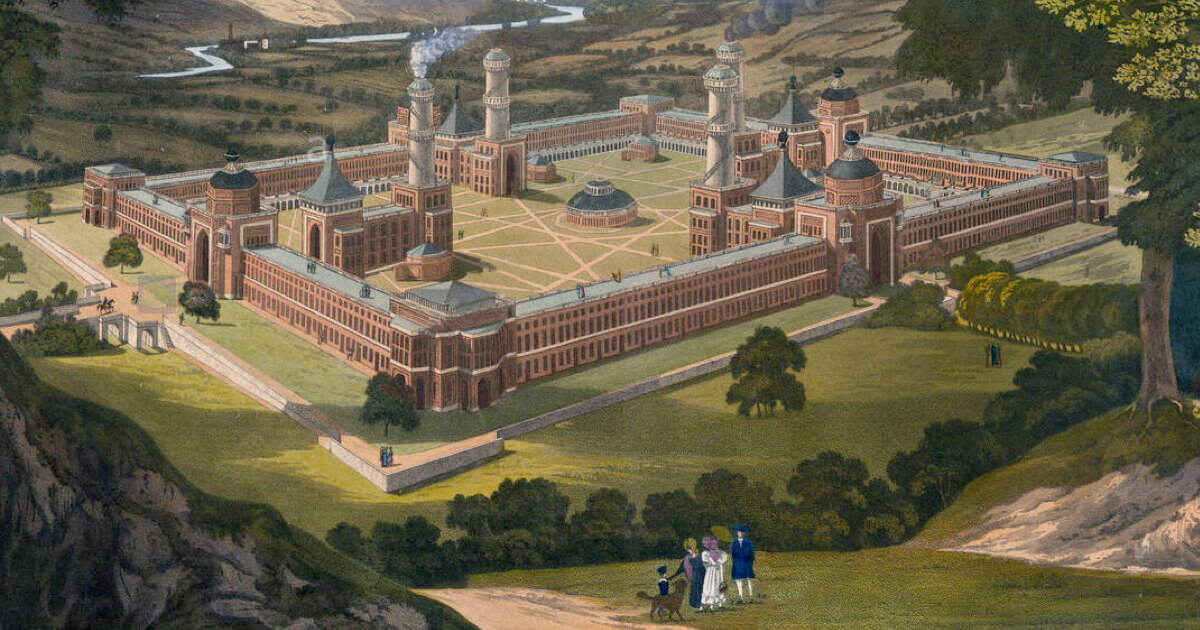

The distinction between Utopian Socialism and Scientific Socialism was made in Friedrich Engels’ book “Socialism: Utopian and Scientific.” Engels discusses some of the early pioneers of socialism such as Robert Owens. For instance, Owens was a wealthy philanthropist who decided to start a workers’ cooperative community with humane working hours and decent wages, and so on in order to prove it’s possible to build socialism based on principles. Engels describes Owens as a Utopian Socialist because Owens believes he can build a socialist society from scratch based on persuading people to accept his conception of a just and ideal society based primarily on “Reason.”

Engels describes the mentality of Utopianism as follows:

“The great men, who in France prepared men’s minds for the coming revolution, were themselves extreme revolutionists. They recognized no external authority of any kind whatever. Religion, natural science, society, political institutions – everything was subjected to the most unsparing criticism: everything must justify its existence before the judgment-seat of reason or give up existence. Reason became the sole measure of everything. It was the time when, as Hegel says, the world stood upon its head; first in the sense that the human head, and the principles arrived at by its thought, claimed to be the basis of all human action and association; but by and by, also, in the wider sense that the reality which was in contradiction to these principles had, in fact, to be turned upside down. Every form of society and government then existing, every old traditional notion, was flung into the lumber-room as irrational; the world had hitherto allowed itself to be led solely by prejudices; everything in the past deserved only pity and contempt. Now, for the first time, appeared the light of day, the kingdom of reason; henceforth superstition, injustice, privilege, oppression, were to be superseded by eternal truth, eternal Right, equality based on Nature and the inalienable rights of man.

We know today that this kingdom of reason was nothing more than the idealized kingdom of the bourgeoisie; that this eternal Right found its realization in bourgeois justice; that this equality reduced itself to bourgeois equality before the law; that bourgeois property was proclaimed as one of the essential rights of man; and that the government of reason, the Contrat Social of Rousseau, came into being, and only could come into being, as a democratic bourgeois republic. The great thinkers of the 18th century could, no more than their predecessors, go beyond the limits imposed upon them by their epoch.”

Engels was more or less explaining an outlook of many thinkers of the Enlightenment involved in a highly rationalist project which aims to construct a just society based on principles discovered through reason as opposed to traditions, authority, and divine revelation. Utopian socialists such as Robert Owens inherit the Enlightenment mentality of building a society based on principles discovered through pure reason. He attempts to build a society of worker’s cooperatives with decent wages, decent working conditions, and trade unions based on his supposed rational intuition of conceiving a just society. In contrast to Utopian Socialists like Robert Owens, Engels presents Marx and his version of socialism as “Scientific Socialism.” Engels describes “Scientific Socialism” based on the scientific method of dialectical materialism (and by extension historical materialism) to understand the “motion” of society.

Dialectical Materialism is the theoretical framework that understands that material reality is under constant flux. This constant flux is primarily due to the fact that every macroscopic phenomenon contains opposite tendencies or “contradictions” that are in constant tension with one another. For instance, under certain conditions, an ice cube has a tendency to maintain its structural integrity, but it also has an opposite tendency to lose structural integrity. As an ice cube’s surrounding condition changes, in particular the temperature of an ice cube’s environment, an ice cube’s tendency to lose structural integrity via melting becomes the dominant tendency over its other tendency to retain structural integrity. When one tendency becomes dominant over the opposing tendency, this leads to a qualitative change.

The application of dialectical materialism to societies (as opposed to inanimate objects like ice cubes) is to conceive society as being in constant flux primarily due to the internal “contradictions” or opposing tendencies within each society. This application of dialectical materialism to society is called historical materialism which sees that each society changes when its mode of production (e.g. a combination of social relations and productive forces) changes due to the struggle between the exploiters and the exploited. When the exploiters are dominant, a society’s mode of production is being maintained. But when an exploited class gains an upper hand under certain extreme conditions, a society’s mode of production radically shifts toward a new mode of production. This is a gist of historical materialism or the application of dialectical materialism to societies.

Engels believes this methodology is scientific as opposed to utopian because it carefully and systematically tracks the development of society to predict what kind of society it would develop into. A utopianist simply attempts to build a just society based on principles discovered through reason as opposed to tradition, authority, and divine revolution. But this approach implies that it is possible to build a just society in the vacuum. A scientific socialist like Engels believes that one can’t build a socialist society without proper conditions. A society must be at a certain stage of development before it can radically transform into a socialist society. What is this stage of development in which there are proper conditions for a society to develop into socialism? This is dependent on the overall situation. In the context of Western Europe, Marx and Engels believe that a society must reach capitalism before it can become socialist. But Marx also believes that in regions outside of Western Europe, the proper conditions for a society to develop into socialism could vary from ones in western Europe. Marx wrote a letter to a Russian revolutionary Vera Zasulich in which he explains that Russia has satisfied its own proper conditions to develop into socialism. In particular, Marx argues that Russia has communitarian peasant communities where some form of social ownership over agrarian productive forces exists. This form of social ownership is a material basis for socialism in Russia. This is an example of the scientific socialist mindset of historical materialism, the application of dialectical materialism to societies.

Marxism is “scientific socialism” insofar as it carefully and systematically tracks the development of a society based on its own particular history of class struggle. Its opposite is Utopian Socialism which doesn’t carefully and systematically track the development of society in order to build socialism, but rather attempts to artificially conform society to an abstract and idealized conception of a socialist society based on pure reason or intuition. In other words, a Marxist tries to be attentive to a society’s own particular trajectory based on its own particular history of class struggle whereas a Utopian socialist tries to artificially impose an idealized conception from socialism based on pure reason or intuition. A Marxist believes one can’t just build socialism, but rather one must be attentive to the condition of society in order to know when it is appropriate to build a socialist society. When conditions are such that an exploited class is becoming class conscious and a capitalist society is no longer functioning well, a Marxist would say that this would be an appropriate opportunity to build up to a socialist revolution.

Radical liberalism is a variation of Utopian Socialism. Liberalism emerges from the utopian mindset of the Enlightenment. A liberal theory which argues in favor of private property rights, individual liberties, and a republic based on principles derived from reason is an approach many Enlightenment thinkers take. A radical liberal is similar to the Enlightenment thinkers insofar as a radical liberal develops an ideal conception of a just socialist society and attempts to impose it on an actually existing society. What makes a radical liberal different from many Enlightenment thinkers is that a radical liberal recognizes the limits of modern-day liberalism inherited from Enlightenment thinkers. The formal bourgeois rights of right to private property and individual liberties aren’t enough to address current problems in society, but rather liberalism is used by the ruling class to historically maintain the oppressive status quo. A radical liberal rejects modern-day liberalism in favor of something that goes further than modern-day liberalism. A radical liberal favors some ideal conception of social justice that goes beyond the framework of abstract individual rights in order to recognize the rights of oppressed social groups. This conception of social justice also includes an ideal conception of a socialist society in which oppressed groups no longer face oppression.

While a radical liberal is quite different from a contemporary liberal insofar as a radical liberal rejects liberalism as bourgeois and reactionary, a radical liberal still inherits the overall utopian outlook of the Enlightenment tradition from which liberalism emerged. A radical liberal has an idealized conception of social justice and by extension an idealized conception of a socialist society based on the principles of justice, such as a principle of reparation, developed or discovered from moral intuition.

Many radical liberals who profess to be Marxists abandoned class struggle as a vehicle for a progressive change in society in favor of some idealized conception of social justice that mandates what sort of just society one ought to build. Rather than accepting that socialism is something that arises from an organic revolution carried out by the proletariat’s class struggle against the bourgeoisie, radical liberals tend to believe socialism is something that could be built by a handful of intellectuals, professionals, and activists who can impose their idealized conception of justice unto society. Radical liberals tend to believe that because they have good ideas, including an ideal conception of social justice, they’re qualified to build socialism without participating in class struggle.

One example that’s symptomatic of this outlook is that many radical liberals spend a majority of their time in cultural critiques or cultural discourse. They critique and “police” behaviors, symbols, cultural artifacts (e.g. statues), gesticulation, etiquettes, cultural norms, ideology, and so on that are indicative or symptomatic of an oppressive capitalist society. Radical liberals believe that this cultural approach (vaguely akin to a cultural revolution, but applied to a capitalist society rather than a socialist one) will raise public consciousness against the system. This is just one among many examples of radical liberals imposing their idealized conception of social justice upon society with the hopes that it will lead to a better society (possibly even a socialist one) without involving the proletariat as the revolutionary agent. This approach is what some Marxists like Gus Hall (who wrote an essay Crisis of Petty Bourgeois Radicalism) would deride as Petty-Bourgeois Radicalism.

Petty-bourgeois radicalism is the tendency among radicals to attempt to bring about change without organizing and mobilizing the broader proletarian communities. It involves an outlook in which the revolutionary agent is no longer unequivocally proletariat, but rather the revolutionary agent is much more amorphous, heterogeneous, malleable, and ambiguous. The outlook is more or less idealist insofar as it believes that artificially imposing good ideas or artificially conforming society to an ideal society is the primary method for change. This is contrary to the Marxist outlook which sees that the method for progressive change is to use class struggle by the proletariat against the bourgeoisie as the social vehicle for social change.

A radical liberal, then, is a petty-bourgeois radical with an idealist outlook on social progress in which the proletariat carrying out class struggle is no longer the primary social force for change, but rather it’s some idealized conception of social justice being artificially imposed on society. Just as Robert Owens tried to change society to a socialist society with his idealized conception of justice carried out through his bourgeois philanthropic methods, a radical liberal tries to change society by imposing their idealized conception of justice through their methods of petty-bourgeois radicalism.

Republished with permission from Midwestern Marx.