You’ve downloaded a few books and are neck-deep in “theory.” Most of the concepts seem to be clicking – wages, economics, commodities, the history – but you keep coming across a term you’re not familiar with: dialectical materialism.

After doing some research, you find yourself a bit confused.

Why would I – or working people in general – want or need to know this?

Learning how to think

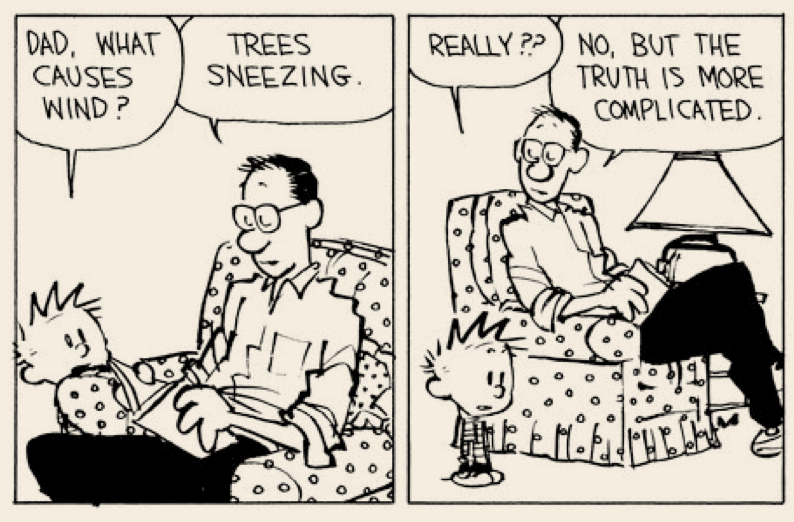

Not only are children in American schools taught what to think, they are taught – intentionally or not – how to think.

From day one of their school experience they are injected into a structured set of rituals, systems, and traditions based on decades and decades of momentum and constant evolution to better suit the ruling class’ needs.

The manner in which teachers (also educated in the school system) answer students’ questions, how their textbooks are written, the way essay prompts are worded, the illustrations and posters in the classroom – they all contribute to a prevailing mode of thought and method of navigating reality.

This mode for the United States? Idealism.

Idealism vs Materialism

There are two primary schools of philosophical thought: idealism and materialism. The difference between the two depends on the answer to the question, “what is the relationship between consciousness and existence?”

In short, idealist thought considers some “spirit” (consciousness, ideas, thoughts, deities) the source of everything, with matter (stuff!) being secondary to that spirit.

Materialist thought is the opposite: it considers matter separate from the world of ideas and consciousness, with ideas and “spirit” being subordinate to matter.

“I think therefore I am” versus “I am therefore I think.”

Idealist thought has existed since the days of primitive man, but one would think that it’d slowly disappear with the advancement of science…right?

Wrong…

Idealism for the capitalists, materialism for the people

These two modes of philosophical thought correspond with the two primary classes: the working class (proletariat) and the owning class (bourgeoisie), with idealism being wielded as a weapon by the owning class against the working class.

A Marxist scholar once put it like this:

…with the development of the productive forces, and the ensuing development of scientific knowledge, it stands to reason that idealism should decline and be replaced by materialism.

And yet, from ancient times to the present, idealism not only has not declined, but, on the contrary has developed and carried on a struggle for supremacy with materialism from which neither has emerged the victor.

The reason lies in the division of society into classes.

Over time, each side of this philosophical coin became a tool for one of the two classes; idealism used by capitalists to keep the workers in the dark, materialism used by the workers to cast light on reality.

Idealism, in the process of its historical development, represents the ideology of the exploiting classes and serves reactionary purposes.

Materialism, on the other hand, is the world view of the revolutionary class; in a class society, it grows and develops in the midst of an incessant struggle against the reactionary philosophy of idealism.

Consequently, the history of the struggle between idealism and materialism in philosophy reflects the struggle of interests between the reactionary class and the revolutionary class.

So what is dialectical materialism?

Basically, it is the study of the motion of matter.

“Dialectical” comes from “dialogue” – a back and forth exchange between two people. We’ve already gone over the “materialism” aspect.

Dialectical materialism is thus a framework for anti-idealist thought. It acknowledges that there is only matter, stuff, that thoughts themselves are composed of matter, and that the motion of all this matter is based on how it interacts with other matter and the contradictions of the matter within itself.

As another Marxist scholar once said:

It is called dialectical materialism because its approach to the phenomena of nature, its method of studying and apprehending them, is dialectical, while its interpretation of the phenomena of nature, its conception of these phenomena, its theory, is materialistic.

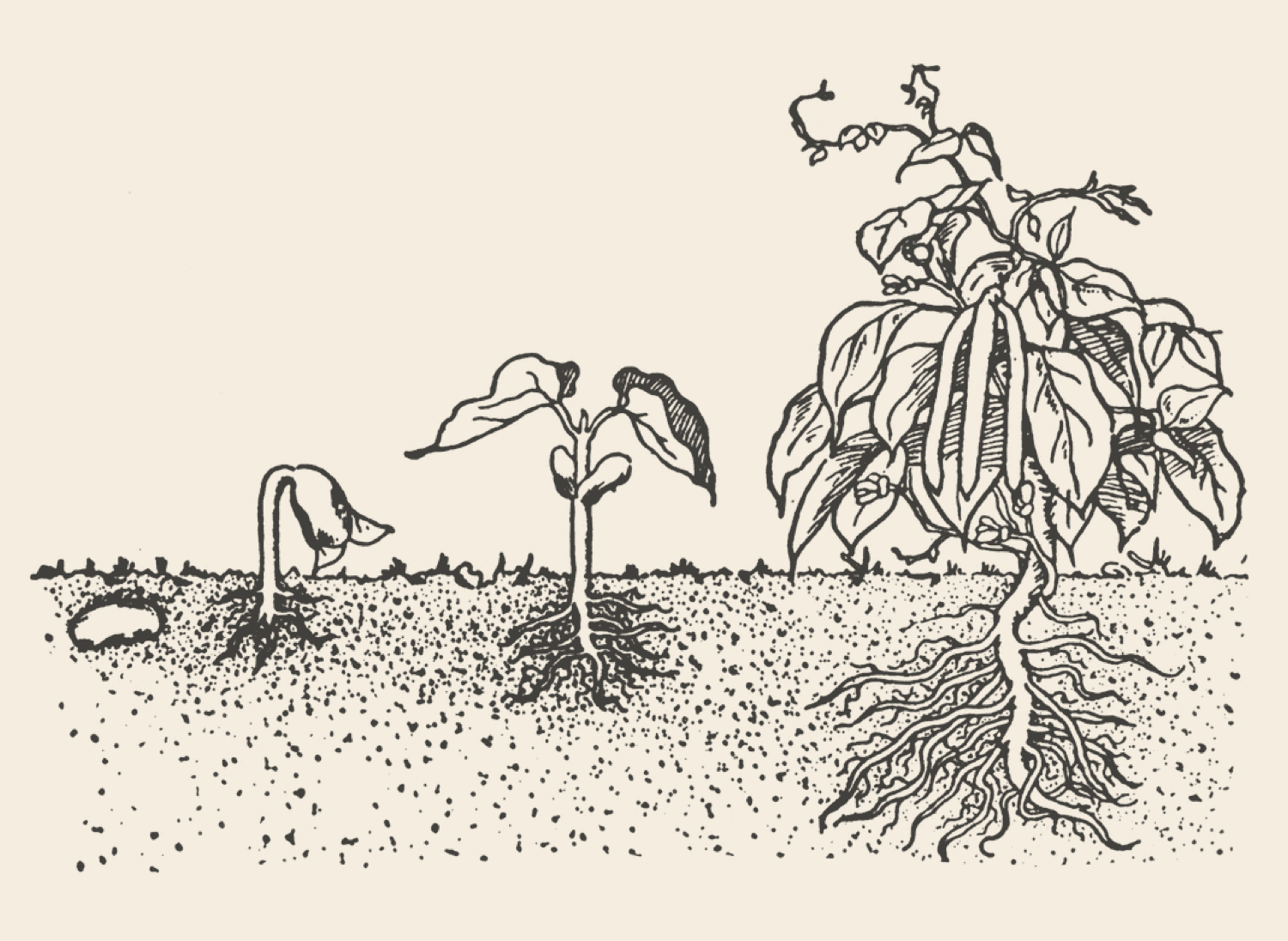

Thinking idealistically, it’s easy to view a green bean as “just a bean” – a thing frozen in time with a fixed set of properties. Whereas when we view it through a dialectical materialist lens, we see the green bean as one part of the process of being a green bean plant.

All motion, including life itself, is predicated on the contradictions inherent within the matter that’s moving. A germinating sprout pressing against its seed casing until it bursts, then that sprout pressing against the soil until it sees the sun – struggle between opposites is required for motion.

This analysis based on the struggle of opposites can be applied to all scientific disciplines:

In mathematics: + and —, positive and negative. Differential and integral.

In mechanics: action and reaction.

In physics: positive and negative electricity.

In chemistry: the combination and dissociation of atoms.

In social science: the class struggle.

What’s so bad about idealism and how is it used against workers?

We’ve established that there are two primary schools of philosophical thought and that idealism is the ruling class’ preferred mode of thought for the working class, but why is this the case?

In short, because workers who think idealistically will be wrong more than they’re right. They won’t be able to build the consciousness necessary to change their conditions and this suits the ruling class nicely.

Idealist thought can manifest in the form of overconfidence, not researching an issue enough, making assumptions, believing in prayer alone over action, acting based on superstition, etc.

It’s put into practice daily in the culture war, keeping working class people at each others throats even though neither progressive workers nor conservative workers hold any real power and have nothing to gain by fighting.

Idealism is easy. It’s far less work to simply accept an easy answer without delving into the issue more. This can lead to false-consciousness, low morale, existential dread, and confusion – all of which ensures workers stay passive and disorganized. Even after being told the factual truth about a topic, plenty of people will make the choice to believe what is easier to understand; this mindset and complete lack of curiosity is a product of the schooling system.

Importantly, idealism can lead to the belief that our current system of governance is “the best in the world.” Without deeper research, millions of Americans go right on thinking this even as upwards of 75% live with a negative net worth, indebted for life, and more than one in ten live in abject poverty.

Idealism masks the sordid affairs of U.S. imperialism. Blind nationalism, white supremacy, and xenophobia keep Americans confused and fighting amongst themselves as billions that should be spent at home are spent on wars abroad.

Lastly, it leads to most workers thinking that things are the way they are and you can’t change them. Can you see how that would benefit the ruling class?

Dialectical materialism gives workers a lens through which to view a constantly changing reality. It is our tool to wield against the bourgeoisie.

Doesn’t the bourgeoisie employ dialectical materialism in science?

Absolutely. Because it is necessity in understanding the material world and how everything on earth interacts and operates together. Many scientists already use dialectical materialism without even realizing it.

It could be said that dialectical materialism is very, very deep analysis. Going through the time and effort to understand:

- the thing itself in its development and in its relations to other things,

- the contradictory forces and tendencies within the thing (what struggles drive the motion of the thing),

- the break-down of the separate parts and the totality (studying not only the whole, but the parts that make it up),

- the apparent return to the old (a seed eventually becomes a tree which again bears seeds),

- the struggle of content with form (appearances versus what something really is)

When necessary, the ruling class requires dialectical materialism in order to advance science and technology in general. They’re even happy to employ it in education from time to time, however, they do not apply it to society as a whole, saying instead that capitalism is the “end of history.”

Seeds, spirals and earthquakes

Dialectical materialism helps us understand the motion of development.

Take the oak tree: from acorn, to germination, to seedling, to sapling, to mature tree, to acorn again, at no point does the organism abolish its previous forms, it sublates them. That is, it incorporates and resolves its own contradictions, transforming into its next stages.

Often when reading about dialectical materialism you’ll see metaphors and references to spirals. This comes from philosopher Georg Hegel who talked about the “negation of the negation.” Developmental processes can seem circular, but as the end becomes the beginning, a newness arises.

In our acorn example, the acorn’s negation is its germination underground; the acorn loses its acornness in exchange for saplingness. Before too long the sapling has grown enough to be considered a mature tree, losing its saplingness in exchange for treeness. That tree will soon drop acorns, starting the process again, but anew.

Hegel said:

The bud disappears when the blossom breaks through, and we might say that the former is refuted by the latter; in the same way when the fruit comes, the blossom may be explained to be a false form of the plant’s existence, for the fruit appears as its true nature in place of the blossom.

The ceaseless activity of their own inherent nature makes these stages moments of an organic unity, where they not merely do not contradict one another, but where one is as necessary as the other; and constitutes thereby the life of the whole.

This leads to an important concept for the working class: not out, but through.

We won’t “abolish” capitalism or “end” society in order to create a new one. Not only does this mindset scare off good workers and give an excuse to the ruling class to insinuate workers just want to blow everything up without a plan for afterwards. It’s also flat-out incorrect and based on idealist thinking.

In the same way an acorn doesn’t stop being an acorn to become a sapling, workers won’t stop society to start a new one. The contradictions already present will be exacerbated until society is forced to reorganize in order to resolve the contradictions, this process being called revolution in this context.

We see this across nature and society:

- Snow falls and falls until an avalanche starts

- Tectonic plates stick as they pass over each other until they suddenly slip, causing an earthquake

- Corn kernels heated in an oiled pan sit idle until they pop

- Members of the same species separated by a river will evolve until they can no longer reproduce with the original population

- Water on the stove sits placid at 211º but begins to boil at 212º

- Outside, water at 33º stays liquid while water at 32º freezes solid

Tiny, sometimes imperceptible, quantitative changes can lead to qualitative changes.

What good does dialectical materialism do for workers?

It can provide hope through understanding. When doing organizing work or party-building, it’s easy to get down about progress. But as we just demonstrated, quantitative changes lead to qualitative changes. If your small steps are in the right direction, they can lead to major progress.

It can provide illumination on major issues and events. When planning and analyzing for a campaign (say, union organizing or getting a ballot initiative passed), dialectical materialism demands that workers understand the many facets of the problem, the history of events leading up to the current state of things, what has been tried in the past, what has worked elsewhere, and the various stakeholders interested in maintaining the status quo.

It gives us the knowledge that everything can change. The ruling class wants desperately for us to believe that things are unchanging, stagnant, the way they will always be. But with a firm grasp of dialectical materialism, this blatant lie dissolves before our eyes. Everything is always changing, including society and the structures within it.

It gives us back the relationships we may have severed due to an idealist mindset. We all have family and friends who hold less than savory views. With an idealist mindset, it’s simple to write them off as “stupid” and move on with your life. With a dialectical materialist view, it becomes obvious that people have had their opinions altered by billionaires in control of tv, web, and social media – our loved ones are victims of the ruling class’ ability to manipulate messaging across networks. With effort, their minds can be changed again.

More profoundly, dialectical materialism provides the knowledge and perspective that we are all interconnected, parts of a larger material process occurring on planet earth. With a solid understanding of it, no longer are we atomized individuals, but constituent parts of a larger whole.

Idealism is the cloudy, cracked lens handed to the working class by the bourgeoisie: pre-sabotage for all future attempts at organizing.

Dialectical materialism is its crystal clear replacement and, when widely understood and adopted, will focus the will of the American working class into an actual political and economic force.

Bean sprout image from John W. Ritchie Primer of Physiology, 1918 via usf.edu. Calvin & Hobbes images Fair Use (non-profit educational). Welder image from Pexels.