In a 1912 pamphlet entitled – rather unimaginatively– N*gger Equality , Kate Richards O’Hare championed what might today be referred to as the Great Replacement Theory.

In Kansas City black men have replaced white men in the packinghouses wherever possible, and the white daughters of both Republican and Democratic voters are forced to associate with them in terms of shocking intimacy. In the coal mines of the whole United States black men have been used to replace white miners until there is not a shred of race distinction left.

To stanch whites’ loss of social standing, O’Hare unsurprisingly proposed strict enforcement of segregationist mores. What may surprise you, however, is that O’Hare was an ardent Socialist at the time she published her pamphlet, writing emphatically:

SOCIALISTS WANT TO PUT THE NEGRO WHERE HE CAN’T COMPETE WITH THE WHITE MAN.

And perhaps just as astonishing is that there was no public rebuke of O’Hare’s racist remarks, no censure from her white Leftist comrades, or sanctions handed down by party operatives. Indeed, her pamphlet seemed to be no more than a faux pas –saying the quiet part out loud –that was entirely consistent with the Socialists’ unwritten policy of pretending that racism did not significantly weaken working-class movements by pitting one employee against another.

No less an authority than Eugene Debs subscribed to this strategy, writing in the International Socialist Review in 1903: “The history of the Negro in the United States is a history of crime without a parallel.” And yet, “(t)here is no Negro question outside of the labor question. . . The class struggle is colorless. The capitalists, white, black and other shades are on one side and the workers, white, blacks and all other colors, on the other side.”

W.E.B. DuBois, who was briefly a Socialist, wrote of the party’s bizarre tone -deafness: “No recent convention of Socialists has dared to face the Negro question fairly.”

The Red Summer of 1919 put paid to the lie of a monochromatic class struggle as thousands of hysterical white workers took to the streets around the country over the course of the year to lynch, beat, shoot and burn to death more than 250 of their African American coworkers who they feared were replacing them in the workplace.

One-hundred and ten years after O’Hare published her racist polemic, another white woman with ties to the political Left in the U.S., Krystal Ball, appeared on the Marxist economist Richard Wolff’s podcast to once again downplay the role that racism plays in the struggle between capital and labor.

“I am of the opinion that there is no war but class war,” she said. “It’s too easy to say that culture war issues … like gun rights or abortion or white supremacy, that these are distractions. What I think they are instead is they mask these deeper issues of class and of economics and of distribution.”

While far more nuanced than O’Hare’s, Ball’s viewpoint is nonetheless an attempt to gaslight what is, by virtually any measure, an apartheid state in which jobs, opportunities and advantages accrue to the whitest and not necessarily the best. If capitalism in its most molecular form is defined as a war between master and slave, then racial capitalism represents a codicil to this arrangement whereby half the slaves believe that they are, in fact, the master, as the late, Marxist historian Noel Ignatiev was fond of saying. Another Marxist historian, Philip Foner, elaborates further in his classic text, Organized Labor and the Black Worker, 1619-1981:

When the president of the Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills in Atlanta, with 1,400 employees, hired 20 Negro women to work in the folding department of one of the mills in 1897, the entire white workforce (went on strike). The company agreed to fire the black workers on one condition: the white workers would have to work overtime for free.

From cotton to cars to credit, the principal commodity may change but white racism remains, as the assassinated black revolutionary George Jackson once wrote, the biggest barrier to forming a cohesive workers’ movement in the U.S. The result is two nations in one, with whites’ overall living standards rivaling Canada’s or Western Europe, while blacks live a life that is closer in quality to Mexico or Palestine.

The dilemma for white –and white-adjacent – Leftists such as Ball and her fellow journalists Glenn Greenwald, Matt Taibi, and Zaid Jilani, retired political science professor Adolph Reed, the founder of Jacobin magazine, Bhaskar Sunkara , and a cottage industry of racism deniers who orbit around the Democratic Socialists of America, is how to claim solidarity with the broader working class while pursuing an agenda of liberal reforms that leaves white privilege more or less intact?

The white Left’s bad faith dates back to at least the days of O’Hare and Debs and has increasingly stupefied Americans’ public discourse, as evidenced by O’Hare’s hot take on N*ger Equality, Hannah Arendt’s baffling dismissal of efforts by African American parents in Little Rock, Arkansas to improve their children’s education by desegregating the public schools (she wrote that they were mere social climbers trying to keep up with the white Joneses) and Ball, who has co-anchored several internet news programs that include Rising, where she interviewed the writer Jilani in 2021 days after a 21-year old white gunman murdered eight people at an Atlanta massage parlor, six of whom were Asian women. Said Jilani at the time:

“There is not a white supremacist wave of terrorism or hate crimes or anything like that.”

That is, in fact, exactly what is happening according to the FBI, the Southern Poverty Law Center, and a 2020 study published by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, which found that

. . . “Right-wing extremists perpetrated two-thirds of the attacks and plots in the United States in 2019 and over 90 percent between January 1 and May 8, 2020.”

Aping Arendt’s excoriation of Little Rock’s black parents, Ball doubled down on Jilani’s exoneration of whites, putting the onus on African Americans who are jealous of Asians’ success, saying:

There is a history of tension sometimes between minority groups and that’s a very uncomfortable conversation to have . . . you’ve got people who are poor in largely black communities who see people coming in and doing somewhat better than they are.

In a report published in March of 2021, Columbia University sociologists, Jennifer Lee and Tiffany Luang pushed back against the “(t)rope of Black-Asian conflict,” identifying a strong correlation between xenophobic attacks and white nationalists. Moreover, the sociologists wrote, both Asians and blacks across the country have worked to mend fences since a Korean merchant was sentenced to probation for fatally shooting a 15-year-old African American girl, Latasha Harlins, in 1991, helping trigger the Los Angeles riots a year later. Consequently, Asian-Americans are among the country’s most stalwart supporters of reparations for blacks, and blacks are among the first to volunteer to accompany elderly Asians on their errands to help deter racist attacks. Lee and Luang wrote:

Hence, not only does the frame of two minoritized groups in conflict ignore the role of white national populism , but it also absolves the history and systems of inequality that positioned them there.

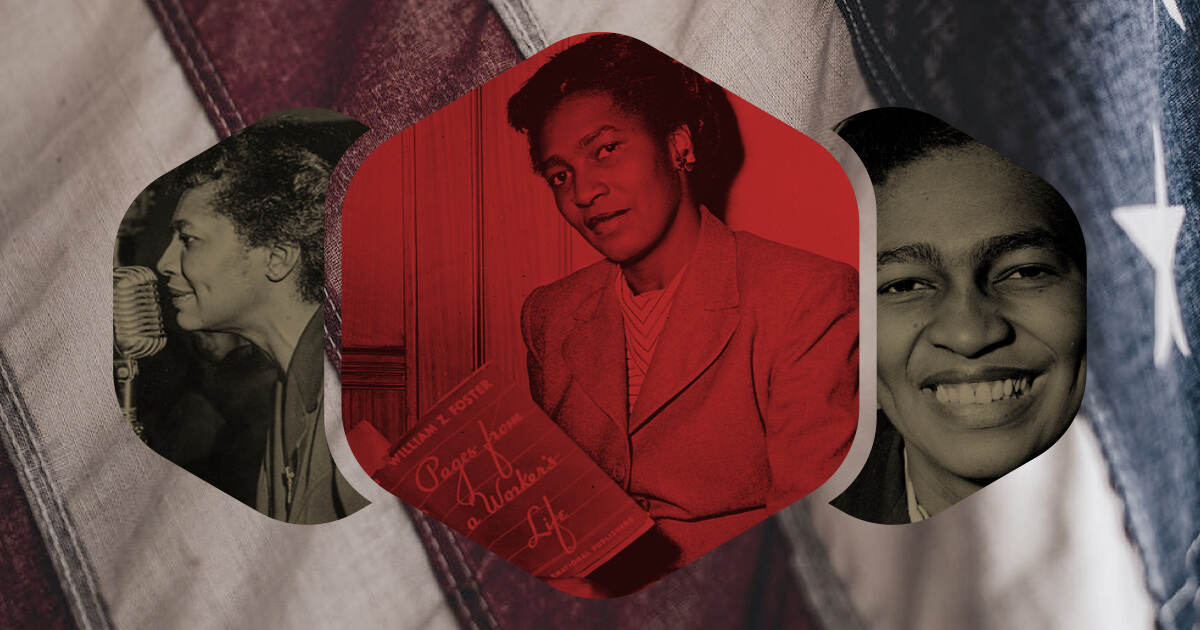

The Communist Party in the U.S. was born during Red Summer of 1919 when the Socialist Party expelled militants who found Bolshevism a more promising fix than either Debs’ colorblindness, or Marcus Garvey’s narrow black nationalism. Scores of African Americans enrolled in Moscow’s Communist University of the Toilers of the East –known by its Russian acronym KUTVA – opened in 1921 by the Bolsheviks to train revolutionaries such as Ho Chi Minh, Jomo Kenyatta, and Deng Xiaoping, and to effectively decommission the “prison house of nations” as tsarist Russia had come to be known, for the ethnic and religious tension promoted by the ruling classes in an effort to keep the workers from rising up together to overthrow the government. Much of the anti-Semitism that defines Ukraine’s neo-Nazi factions today, are in fact, rooted in Ku Klux Klan-like organizations such as the Black Hand, which terrorized Jewish communities for decades with nighttime pogroms.

Vladimir Lenin knew that the revolution would not stand if the Republic remained divided, but unlike the Socialists in the U.S., the Bolsheviks did not gaslight the population’s ethnic differences, they celebrated them. While this enthusiasm would ultimately wane under Stalin, the early years following the 1917 revolution were informed by a level of class solidarity that identified bigotry and racism as unpatriotic, or even subversive.

In his autobiography, Black Bolshevik, an African American named Harry Haywood, who studied at KUTVA, recalled a drunk staggering aboard a half-empty Moscow streetcar one late afternoon in the late 1920s. Seeing Haywood with a group of his black classmates, the inebriate mumbled loud enough for everyone to hear “Black devils in our country.” Here is what happened next, according to Haywood:

What then occurred was an impromptu, on-the-spot meeting, where they debated what to do with the man. I was to see many of this kind of “meeting” during my stay in Russia. It was decided to take the culprit to the police station, which, the conductor informed them, was a few blocks ahead. Upon arrival there, they hustled the drunk out of the car and insisted that we Blacks, as the injured parties, come along to make the charges. At first, we demurred, saying that the man was obviously drunk and not responsible for his remarks. “No, citizens,” said a young man . . . “drunk or not, we don’t allow this sort of thing in our country. You must come with us to the militia (police) station and prefer charges against this man.”

The car stopped in front of the station. The poor drunk was hustled off and all the passengers came along. The defendant had sobered up somewhat by this time and began apologizing before we had even entered the building. We got to the commandant of the station.

The drunk swore that he didn’t mean what he’d said.” I was drunk and angry about something else. I swear to you citizens that I have no race prejudice against those Black gospoda [gentlemen].

Rather than parroting O’Hare’s cynical approach to class struggle, perhaps the 40-year-old Ball could model her efforts on the Bolsheviks, or if that is a bit too far afield and too long ago, she might consider the experience of another winsome young, white woman, Bernardine Dohrn, who as a 27-year old graduate of the University of Chicago’s Law School, exhorted her comrades in the Students for a Democratic Society to raise their revolutionary metabolism at a 1969 meeting:

“The best thing that we can be doing for ourselves . . . and the revolutionary black liberation struggle, is to build a fucking white revolutionary movement.”

Originally published on the author’s Patreon. Republished with permission from Black Agenda Report.