Marx studied UK manufacturing industries, at that time the most representative of world capitalist development, unveiling the general law of the development of capitalist societies more than 150 years ago.

The economic and industrial structures of the capitalist countries have evolved dramatically; by the early 1990s, the share of the service industries in GNP had risen from 20-30% in the developed countries over a century ago, to 60-70% in those countries, 50% in the semi-developed countries and 34% in China. Trade in services has risen to 25% of the global trade volume and is expected to continue growing.

Since the service industries exert great influence over a country’s economic development and job market, we should devote increased effort to studying them from the perspective of economic theory. This is a complicated undertaking, because research into the theoretical aspects of the service economy still falls short of expectations, accompanied by wide and deep-rooted differences of opinion, in all schools of thought. This is because of the particularity of the service industries, the changes they are undergoing, and the growing universality of their scope.

Historical review of theories of the service economy

We shall now address the two main bodies of theory relating to the service economy: Marx’s, and those of Western scholars. Because of the differences in their research goals and subjects of study, they differ widely.

Marx’s theory of services

As noted, Mars made material goods production his main research area in his studies of the socioeconomic problems of capitalist societies in Capital, singling out the British textile industry for special treatment. He pointed out that the production of wealth by capitalist societies was characterized by large stocks of self-evidently tangible commodities. These could be accumulated over a long period of time, they could exist in the absence of producers and consumers, and they were transportable.

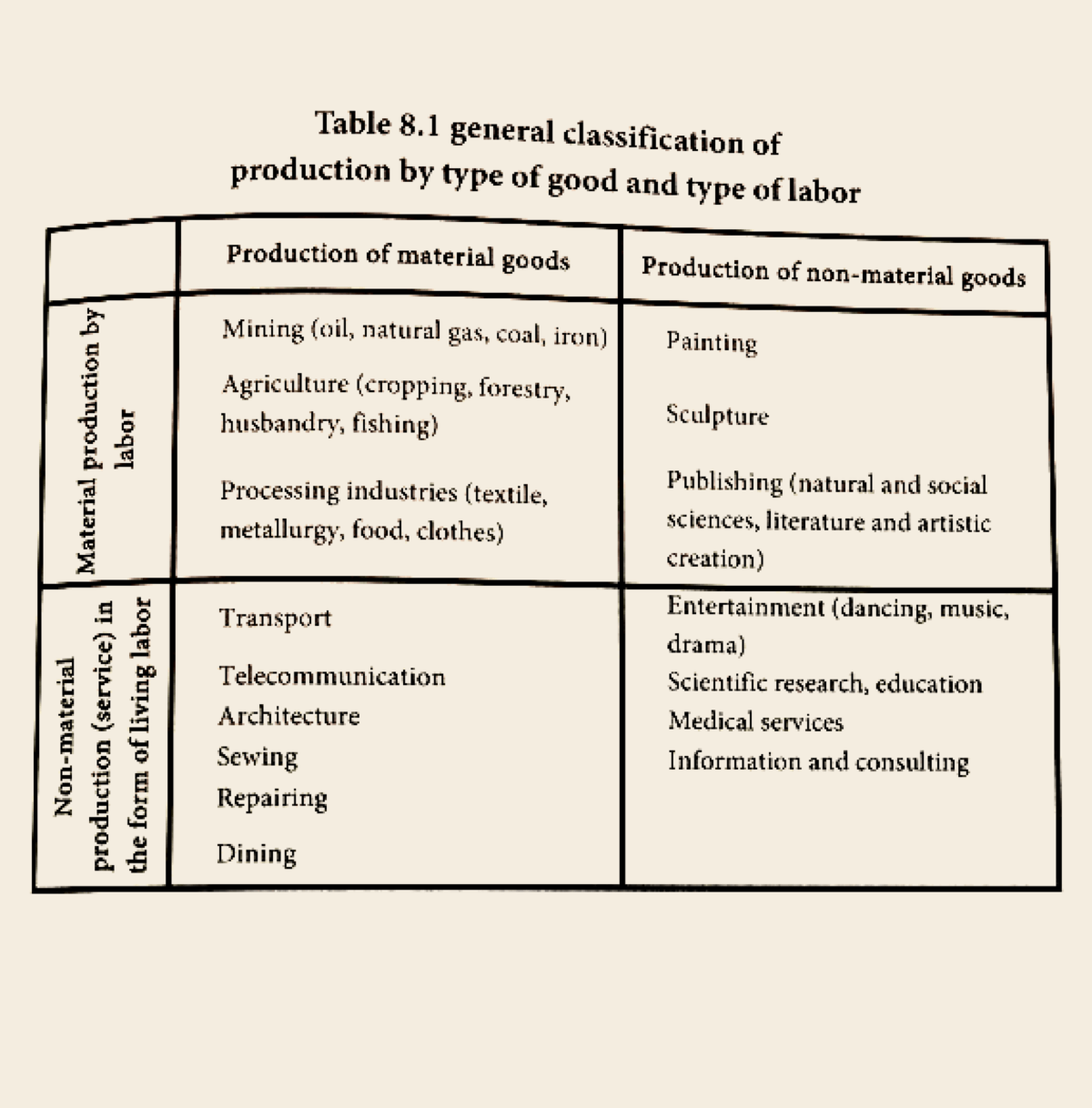

Products can be divided into material goods such as clothes, automobiles, and planes which exist independent of other factors, and non-material goods such as transport and communication, which exist in the form of living labor from which they cannot be separated. As Marx wrote, “in addition to the mining industry, agriculture and processing industries, we also have the fourth area of material goods production …. which was transport” (Marx and Engels 1972c, p. 444).

This suggests that transport can be classified in the same area as mining, agriculture, and processing whose purpose is to extract materials from nature. It does not actually produce or provide material goods, but creates products in the shape of living labor, which provide the intangible use value of changing the spatial location of material goods, so that these can be delivered to consumers as consumer goods in a real sense.

As we have noted, there are two types of non-material goods. The first consists of things like books or audiovisual products, which can exist in the absence of producers and consumers. The second take the form of living labor. These goods include live concerts and lectures. Both can be produced as commodities and become products of social labor by entering the exchange system. Marx argued that it was unscientific to define productive labor as that engaged in material production, an idea which he considered a one-sided outcome of Smiths outlook.

Table 8.1 provides a general classification of production based on the above analysis.

The concept of service in economics

The term “service” has wide implications. In economics, it usually refers to the work done in selling and purchasing commodities. More generally, it refers to the use value of a particular type of labor, just as material goods have their own special use value. However, it is called a service because its result is not a material good, but the living labor itself.

This implies that the service provided by labor is no different than, for example, that provided by a machine, such as a clock (Luo 1990, p. 264).

We conclude that service is a particular type of use value, like that provided by other material goods, but taking the form of living labor. Yet if the result is provided without the presence of living labor, for example, as a book, it could be argued that only a material good, not a service, is provided.

Thus, the normal economic definition of a service is not without contradiction. How might we respond? We begin from the following two points.

First, the party providing services and the party receiving services are related through exchange. Second, a service is also a type of commodity not qualitatively different from material goods. The difference lies only in form.

Both types of commodity have use value. However, that of a service is given by the character of the living labor involved, not its material form. A book, for example, has the same content whether it is printed on paper or delivered electronically as an e-book.

We now attempt to clarify these points and resolve these difficulties through a more comprehensive analysis of the concept of “service” and its relation to living labor.

Pure services and non-pure services

The products of labor take two forms: tangible and intangible goods or services. There are two types of the latter. The first is use value in the form of labor that fades away the moment it is provided. For example, suppose a concert is given in Beijing by three well-known tenors. To hear their beautiful singing, customers pay a high price for a ticket; the three tenors sing and they enjoy it. Their enjoyment stops once the singing is over. Since such use value can only be provided for customers in the form of living labor, Marx termed it a “pure service.” But a customer may also choose to purchase a use value directly in the market, or cause it to be produced by purchasing living labor. For example, he might order a suit by choosing cloth and inviting a tailor to make it up into a suit, instead of buying it in the market. Marx treated the latter as an “impure service” in which the living labor used to create use value does not itself necessarily constitute the use value.

Sole-purpose service and not-sole-purpose service

A second distinction concerns whether purchase is for the consumers direct use or for resale. In the case of the tenors, the consumers purchase living labor from a service provider and consume it as pure use value. They do not intend to resell it or its product. A second example is when a family prepares some cloth and invites a tailor to make clothes out of it for family members. These are for family use, not for sale.

A second type of service delivery takes place when the living labor of service providers is used to produce commodities subsequently sold in the market, not for personal consumption. The production and sale of beautiful writing by an individual calligrapher belonged to this latter type of service.

The same applies if a private school employs teachers to give lectures to paying students.

The above distinctions have important economic implications. The first distinction defines two forms of services related to living labor; the service is directly purchased as labor but may be used to produce material as well as intangible goods. Intangible goods are always services, but not all services are intangible. Intangibility is a necessary but not sufficient condition.

This distinction has caused economists great difficulty in analyzing the economic nature of services. They regard the precise definition of services or their scope as an impossible mission. Take for example a consulting firm that employs both a team of economists and a team of computer scientists, and which provides econometric consultation and sometimes software services related to econometric analysis. From the perspective of the labor process, the two types of service are more or less the same, since they consume the living labor of economists and computer scientists. But from the perspective of the outcome of this labor, the two types of service are different.

One is a pure service (consulting) and another (software products) is not. They belong to different statistical categories.

This distinction is more significant as it relates to productive and nonproductive service. Pure service is treated, in economics, as a non-productive service which does not create value. Not-sole-purpose service is treated as productive, creating the value of service products.

In capitalist society, there are some independent producers who are employed by public institutions, or as individuals. As capitalism and S&T develops, it takes over the production of ever more commodities. Like a shining sun it obscured all the obstacles to its progress and becomes the master of social production. In the service sector, employed labor comes to comprise an overwhelming percentage of all service labor.

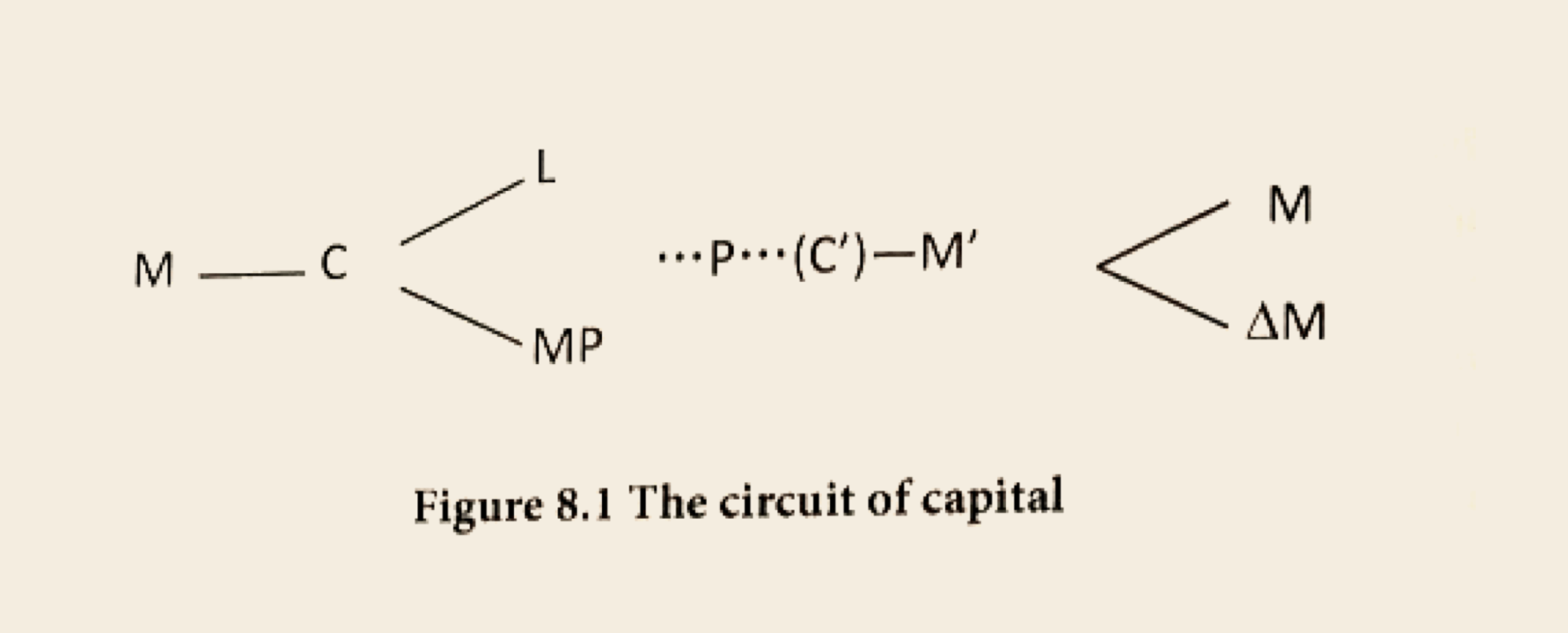

Capital is actually value capable of yielding surplus value. As we have noted, to make capital expand, the capitalist needs labor power, which is combined with elements of production to produces commodities whose value is greater than the sum of the expenditures. Each production cycle follows the previous one, as shown in Figure 8.1.

In the above equation, M stands for the money capital advanced by capitalists, C’ for material goods produced by service labor, L for labor power, and MP for elements of production. P is the process of production. C’ stands for capital goods produced by service labor. M’ stands for the sum of values after the goods have been sold. AM represents surplus value. What really concerns capitalists is to make their capital expand; the different lines of commodities are not that important from their perspective. However, when providing the use value of services, the form of commodities assumes two types: pure services like transport, artistic performance, and processing for customers, and material goods produced by service labor, which we might call a replacement for pure service. The replacement could for example be the clothes produced by a tailor hired by a capitalist.

In addition to the services provided by employed labor, there are also a small number of independent producers in capitalist societies. These independent producers normally command few elements of production.

Laborers in the repair and assembly industry, for example, rely on their technical skills to provide services using a limited number of instruments or tools, often providing door-to-door services. Clearly, such economic relations have nothing in common with exchange between capital and labor.

Although they provide services, belong to the category of productive laborers, and create value, they cannot be regarded as capitalist commodity producers. They are thus neither productive nor non-productive laborers.

Individuals, families, and some public institutions also employ workers to provide various services in both pre-industrial and contemporary societies, providing them with income. However, these funds are either private personal income or, with public institutions, derived from the redistribution of national income. Their labor is consumed as pure use value, providing pure services, not commodities. Indeed, they even receive commodities from the buyers (Marx and Engels 1972c, p. 151). They are thus non-productive.

For all these reasons it would be unscientific simply to divide service-providing labor into productive and non-productive, and irrational to draw a distinction between labor producing services, and labor producing, or directly engaged in producing, material goods.

Western theories of the service economy

As discussed above, research into the economic aspect of service production is complicated by the particularities inherent in the concept of “service” which, just like the term “value, has become a phrase in common popular use. It was not originally an economic term in a strict sense, even though it is widely employed in economics. In fact, Western academic economics has no generally agreed definition of service. In the literature we find three meanings of the word.

(1) If an individual or business provides assistance or use value contributing to the welfare of a recipient, it is said to provide a service.

(2) A service is an intangible good for exchange with a certain amount of exchange value, and its use value is instantaneous (for instance, entertainment), reusable (information), or variable (specialized consulting).

(3) Service is the result of purposeful activities of an individual or a business, which may or may not receive a reward.

Thus the concept has been rather ambiguous and general, and consequently lacking in academic rigor.

The earliest scholar of the issue was Say (2001), who pointed out in A Treatise on Political Economy that intangible goods (services) were also the fruits of human labor and a result of capital. He thus developed a deeper understanding of wealth than Adam Smith – who defined wealth as tangible or materialized goods – dividing such goods into several categories.

The classical economist Bastiat argued, in his Economic Harmonies, that labor and service involve effort and provide satisfaction. They have to be transferable, because otherwise they cannot be provided. However, the proportionality between value and effort has never been evaluated (Bastiat 1996, pp. 76-160). Bastiat further held that capital and labor provide services for each other. To evaluate a service, he suggested two standards: the service provider’s effort and level of stress suffered, and the recipient’s relief from stress.

Marx leveled severe criticism at Bastiat’s economics. In his work, “service” can be used in two ways. It can refer to a particular type of use value – the general usage of the term – or have the specific meaning of the multiplication of capital. The latter focuses on the following point: if labor exchanges with capital rather than income, then it provides services with the special role of creating surplus value (profit) for capital. Marx termed this the service provided by laborers employed by capital for capitalists, and distinguished it from service in a general sense:

“Service is in general only an expression for the particular use value of labor, in so far as this is useful not as a material object but as an activity. There are all entirely indifferent forms of the same relation, whereas in capitalist production the do ut facias expresses a very specific relation between objective wealth and living labor. Hence because the specific relation of labor and capital is not contained at all in this buying of services, being either completely extinguished or not present at all, it is naturally the favorite way for Say, Bastiat and their associates to express the relation of capital and labor.” (Marx and Engels 1972c, p. 435)

Fuchs (1968) was the first to apply classical analysis to the service economy of post-Second-World-War America. He argued that a service is perishable at the time it is produced or created. A service is provided in the presence of a customer. It cannot be transported, stored, or accumulated, thus it lacks substantiality. Although this definition is characteristic-oriented, it fails to state which characteristics of a service are in fact essential.

The marketing guru Kotler (2007) defined a service in Marketing Management as follows: “A service is any act or performance that one party can offer to another that is essentially intangible and does not result in the ownership of anything. Its production may or may not be tied to a material product” This definition has limitations: intangibility being a necessary but pot a sufficient condition for a service, it concerns only the form, not the Content. The provider of service labor temporarily cedes the rights to that labor to the recipient of the service.

Although labor in this form does not result in a material object, the use valve it provides does not differ essentially from that provided by a material object. It does not follow that transfer of ownership is only secured by the possession of material objects: consuming the use value provided by living labor also involves transfer of ownership.

The economist Hill (1997) defined service as a change in the condition of a person, or of a good belonging to some economic unit, brought about by the activity of some other economic unit. Defining a service in terms of its outcome, he does not break free from the shackles of commodity definition, but admits it to be the result of labor, distinguishing his definition from other vulgar economic concepts.

A service is an activity such that the activities of a producer may change the condition of some economic units. This change could be realized by the changes in the material condition of goods owned by a consumer unit. On the other hand, this change may affect a person or a group of persons’ material or mental conditions. Whatever condition, the notable feature of service production was that producers did not add the value to the goods or himself, but added the value to the goods of an economic unit

A service should be provided for an economic unit and this point was inherent in the concept of a service. Service production stood in sharp contrast to the production of material goods. In the production of material goods, a producer may not be fully aware of the end users. A peasant may grow crops in the complete absence of the landlord. But a teacher could not exercise teaching without the presence of pupils.

As for a service, the actual production process must be in contact with an economic unity so as to make the service transacted. (Hill 1977, PP. 315-38)

A common point in service production is that service must be delivered and consumed at the time it is created, sharply distinguishing it from other types of production. In the production of material goods, there is no such limitation. It suggests that a service cannot be added to the producer’s stock of completed goods (Hill 1977, pp. 315-38).

The economist M. Sokolov (1985), of the former Soviet Union, defines service in his Non-Productive Economics such that labor and service have dual implications. “First, labor and service could be understood as a type of particular use value produced by the consumed labor; Second, if labor was to be exchanged with income, then labor and service could be understood as a form of non-productive labor” (Sokolov 1985, p. 221).

The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics (NPDE 4, p. 314) states that:

In everyday language, we make a clear distinction between goods and services. When we refer to services, we tend to think of services rendered to people (classic examples are Fourasties much cherished hairdresser, Baumol’s singer and Pigou’s valet. A more recent use of “services”, namely, business services, refers to the process of externalizing parts of R&D, or management functions. Services are commonly seen as extending to activities like retailing, banking, insurance and non-market activities linked to public and private administration It is, moreover, current practice to include transport and telecommunications within this already vast set of activities …. what is striking is the contrast between the relative simplicity of current usage and the difficulties encountered in defining services within an economic analysis.

Some further definitions in Western textbooks (e.g. Fitzsimmonds and Fitzsimmonds 2006, pp. 3-4) are that a service consists of action, procedure, and performance, or that it is an activity, or series of activities, of a more or less intangible nature that normally, but not necessarily, takes place in interactions between customer and service employees and/or material resources or goods and/or systems of the service provider, which are provided as solutions to customer problems.

Most authorities consider the service sector to include all economic activities whose output is not a material product or construction, which is generally consumed at the time it is created, and in which value is added.

A service emphasizes the intangible interaction between a customer and its providers. It is also argued that a precise definition should distinguish goods from services on the basis of their attributes. A good is a tangible material object or product that can be created and transferred; it has an existence over time and thus can be created and used later. A service is intangible and perishable. It is an occurrence or process that is created and used almost at the same time. Service is also defined as an experience in which a customer acts as a co-producer, and which perishes with time.

There are thus countless definitions of service. However, a common thread is their emphasis on intangibility and synchronicity between production and consumption.

The concept of tertiary industry

In the absence of a consensus even on the definition of services, any study of theories about them is fraught with difficulties. But there is a practical question also: how does the system serve statistical purposes?

Most economic theory recognizes a basic classification of business establishments into three broad categories, expressing the idea that industries sharing similar characteristics should be grouped into broad “sectors”: primary, secondary, and tertiary. There are three general approaches, described below. As we shall see, services are loosely identified with the tertiary sector, but the identification is not rigorous.

The idea of a three-sector classification first appeared in The Clash of Progress and Security by A. Fisher (1939), a British economist and professor at the University of Otago, New Zealand. Shortly after, the British economist Colin Clark (1940) further elaborated this idea in his Conditions of Economic Progress. This classification, and its use in analyzing the economic development of Western countries, found gradual acceptance in Western economic circles and statistical agencies. Nowadays the national economic statistics of the vast majority of countries around the world are based on this basic Classification, notwithstanding variations in economic level and structure.

However, though it may serve to outline the developmental stages of differ. on industries in the national economy, it is not a precise classification in the economic sense, and gives rise to many shortcomings in economic statistics. It also may not help precisely predict the economic level and structure of a country or, on a more general level, facilitate multi-country studies.

The second broad approach is found in the International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities (ISIC) developed by the United Nations and used all over the world, being subsumed under the system of national accounts (SNA). ISIC has gone through four editions, wielding enormous influence on the classification of business establishments of Western countries. Australia, New Zealand, the EU countries, and Japan developed classifications based on ISIC.

The third broad approach, known as the North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS), is based on ISIC. One of its unique points is its capacity to predict new trends of economic development in a timely manner, as it closely monitors the development of emerging industries. It has the potential to be a new standard.

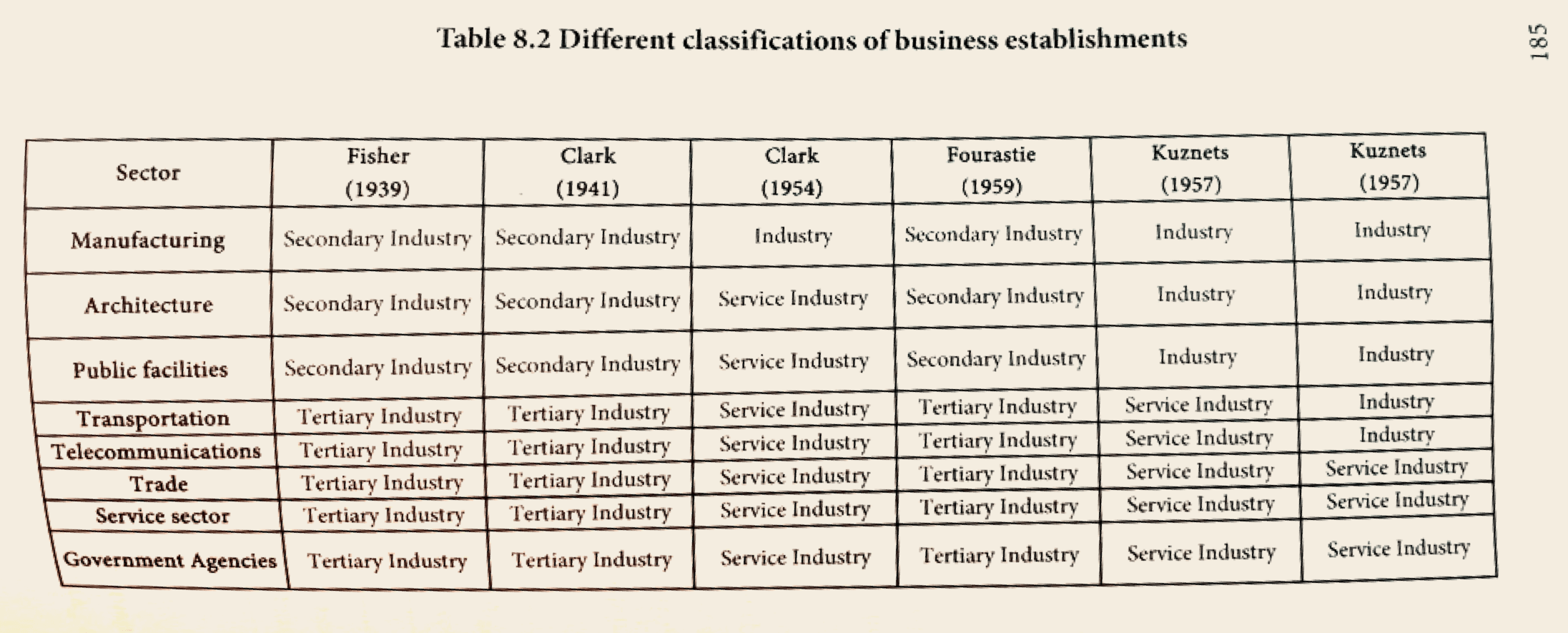

However, economists still cannot agree on the classification of business establishments. Table 8.2 is a brief list of the classification of business establishments by some economists, taken from Huang (2000, p. 65).

Table 8.2 shows that the concept of tertiary industry is not conceptually the same as service industry. The two concepts are mutually related but different from each other. Clark stopped speaking of “tertiary industry” after 1941, and began to use “service industry” instead. His definition is quite close to Marx’s concept of service.

Moreover, while the economists mainly subsume government agencies under tertiary industry or service industry, Kuznets (1999) subsumes transportation and telecommunications under the category of industry, which is consistent with the approach of the classical economists. Marx also took transportation as productive. In terms of the form of labor, however, transportation and telecommunication belong to the service industry.

What type of industry might the concept “tertiary” really refer to? Generally, it is held to include such industries as the following:

- architecture

- transportation

- urban public utilities

- consulting

- entertainment, for example drama and music

- education and public health

- repairing, washing and dyeing

- dining and hotel services

- hairdressing, bathing, photography, and tourism

- commerce, leasing, finance, and insurance

- governmental agencies including defense.

Thus, the concept is not really based on any underlying similarity between these industries. It is defined by elimination, creating a hodge-podge of all business establishments outside mining, agriculture, and manufacturing. In contrast, the concept of service industry is conceptually clear and scientific.

The two concepts are thus different. Tertiary industry is defined by elimination while service industries are normally defined by the form of the labor they employ. Being based on production, a characteristic of the activity of living labor, the second definition is less ambiguous. Tertiary industry is further based on the concept of a supply chain. It implies that economic development normally follows the path from low-level industries to high-level industries, the responsibility of low level industries being to provide the raw materials for high-level industries. The words “primary” and “tertiary” themselves illustrate this point. The concept of service industry is however based on the characteristics of production and the needs of each business establishment. Finally, the economic implications of the tertiary concept are more related to the domestic economy of a particular country, while those of the service concept are more connected with internal and external markets.

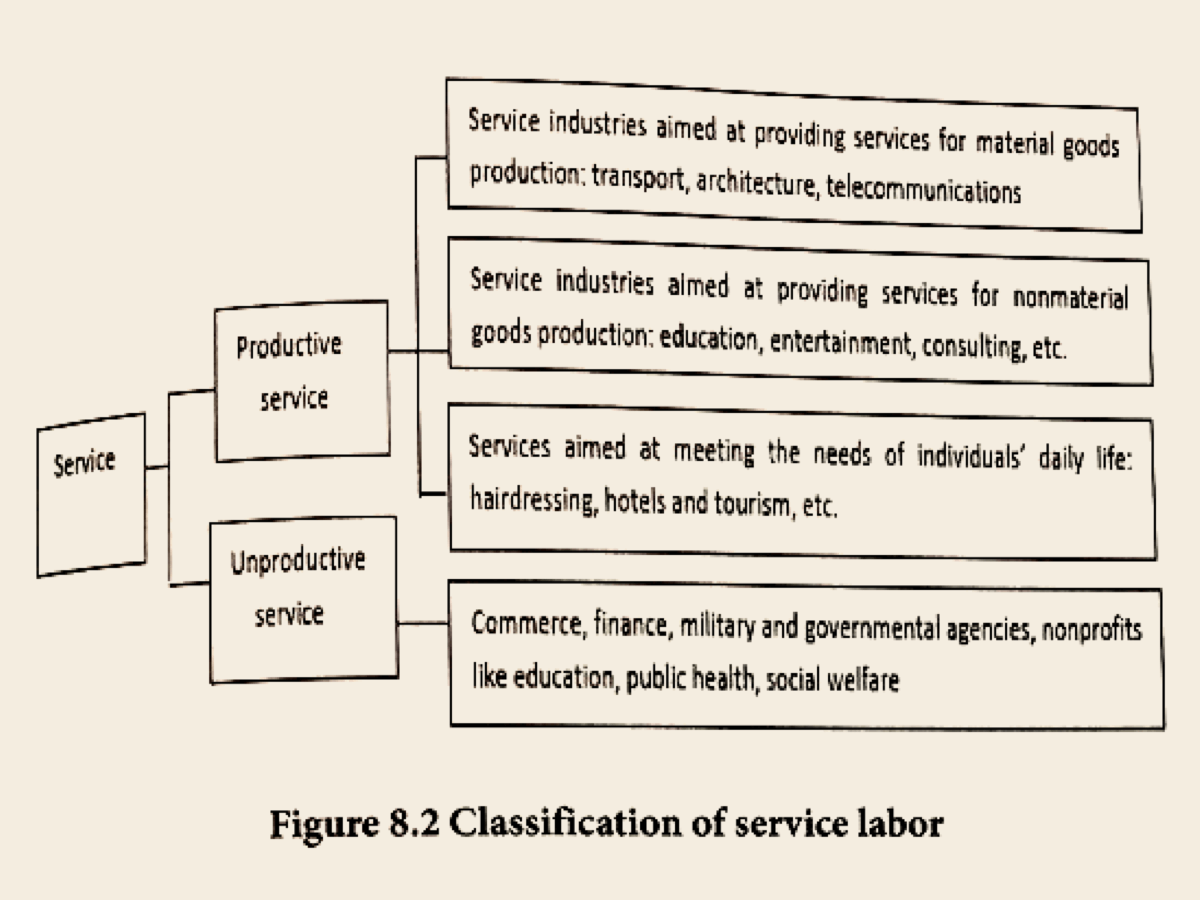

We are now in a position further to subdivide the scope of service industry in social productive systems, as shown in Figure 8.2.

China’s statistical system

We now turn to China’s own system for reporting on the service industries. Does its classification system serve economic statistics efficiently?

China applied the Material Product System (MPS) from 1949 until April 1985, when the State Council agreed the wide distribution of its Report on Compiling Statistics on the Tertiary Industry, marking the beginning of the adoption of SNA. This report subdivided China’s business establishments as follows:

- primary industries: agriculture (forestry, husbandry and fishing industry)

- secondary industries: industry (including mining, manufacturing, running water provision, power, gas, and architecture)

- tertiary industries: all other industries.

- Tertiary industry was further divided into transport and services, covering four areas:

- logistics: this area includes transport, telecommunications, dining, supply and storage

- services to production and consumers, including finance, insurance, material goods census, real estate, public services, civilian services, tourism, consulting and information services, as well as technological services of various kinds

- education and public welfare, including education, culture, broad.

- casting, scientific research, public health, sports, and social welfare services for social needs, including governmental agencies, the Communist Party of China (CPC) and various social organizations, military, and police.

The service industries in China contain hundreds of industries, a full list being beyond our scope. The following is an indicative summary:

- agriculture, forestry, husbandry, fishing, mining, hydraulic systems, transport, storage as well as telecommunications (including railroad, express-ways, waterways and air transport, and support industries such as storage)

- wholesale, retail and catering (including food and beverages, wholesale household goods, power and materials, wholesale mechanical and electronic products, retailing, and agencies)

- finance, insurance and real estate (including development and management)

- social services (including public services, residential service, hotels, leasing, tourism, entertainment, information and consulting applied computer services)

- public health and social welfare, education, culture, arts and broadcasting (including colleges and universities, primary and high schools, broadcasting, film, and so on)

- scientific research and technological services (including natural science research, social science research, multidisciplinary research, meteorology, seismology, field surveys, quality control, oceanography, environmental protection, technology diffusion)

- government agencies, CPC, and social organizations.

Value creation by labor in service industries

Capitalist development has brought about a dramatic transformation of re economic structure of all major market economies, of which a notable feature is the dramatic increase in the share of the service industries in the economy, notably output and employment. This transformation began to attract economists attention some time ago. Fisher (1939) was the first to attempt an in-depth analysis of the history of economic development of the major market economies, which gave rise to his well-known thesis of three stages in the evolution of economic structure.

Clark then conducted a longitudinal study on industrial outputs and labor inputs, advancing the thesis that the agricultural labor force was decreasing while that in manufacturing and services was increasing. Clark’s theory was consistent with William Petty’s central ideas, and became known as the Pettv-Clark law, delineating the relationship between economic growth and the evolution of economic structure. The experience of several countries at different stages of economic development has validated the Petty-Clark law.

In the 21st century, service industries in the developed countries reached 70% of GDP, as the law suggests. China also conforms to the law. By 2001, its service industries accounted for 33.6% of GDP, becoming one of the key sectors and playing an extremely important role in Chinese development. This makes an in- depth study of economic theories related to service industry an imperative. Specifically, breakthroughs are needed on such important theoretical issues as the quality of service products, the nature of service production, value creation in services, and their relation to economic growth.

In the first chapter we developed the concept of service, and established the scientific character of Marx’s definition. A service is a particular form of the use value of labor power. Service is in general only an expression for the particular use value of labour, in so far as this is useful not as a material object but as an activity (Marx and Engels 1994, p. 451).

Service per se does not produce a useful effect in the same way as a material product, but it does produce a useful effect as an immaterial product, namely living labor.

Based on this definition, we hold that service labor should include not only services provided for material production, such as telecommunications and sewing and the services entering cultural production such as performance and painting: but also service labor that circulates commodities and currencies, and services offered by governmental agencies. However, should not include materialized services functioning as inputs to material production, specifically cultural products in materialized form. Since ser. vice labor can be divided into absolute and non-absolute service labor, we also argue that not all service labor creates value. Military and government agencies do not create value. Only productive service labor consumed by individuals or serving as an input into material products (including cultural products) creates value. Our study is confined to productive service labor.

Similarities and dissimilarities between service production and material product production

In material production, with given resources and technologies, producers may turn the subject of labor into real material products with a definite quantity of use value. Therefore, the living labor of laborers is expressed in this use value. To a large extent, these material products and their use value are stripped of the characteristics of their producers and consumers. The former can sell them right away, or keep them for some time. The latter can, correspondingly, start consuming straight after purchase, or delay. They can resell their purchase at a higher or lower price, or send it to other people.

Production, exchange, and consumption thus constitute the whole complex cycle. In this chapter, we take the production, exchange, and consumption of material products as points of reference for an in-depth study of the characteristics of the production, exchange, and consumption of services.

The synchronicity of service production and consumption

The production of material goods is normally undertaken in the absence of any potential consumer. In services, however, production and consumption are not so completely independent, and happen more or less simultaneously. Consumption normally terminates very shortly after production is over. This also makes service labor devoid of an independent exchange process. Under normal circumstances, exchange precedes production, the completely opposite of the exchange of material commodities.

The outcome of production

A pure, or absolute, service creates no material product. For example, go. ins to a concert hall to enjoy a Singer consumes a type of service. But if the labor activity is not an absolute service, as when a software engineer develops a package of management software, the outcome is an alienable product. contrast with a pure service. However, if the software engineer is invited o provide a consulting service for a consumer, their labor is provided as a pure service. It can be concluded that a pure service may not be used for exchange purposes, as may a service which results in an alienable product. Such a characteristic raises two important questions on how to measure service labor, and how to accumulate its effects.

The first question is very important. Most services cannot be further sub-divided, so that there is no obvious unit that can be used for measurement. In some industries, the outcome of the labor provides a measure of the service it produces. For example, the amount of goods carried by the transport industry can be used to compute a rough measure of the output of transport labor. In most cases, this is uncontroversial.

A second characteristic of service labor is also very peculiar. Since its outcome is not material, for the most part it cannot be accumulated. Yet some forms, such as education, produce outcomes which can be accumulated as human capital (Hill 1997). It can thus have a lasting impact.

Individualization

Material production is an independent process undertaken in the absence of consumers. This is the reverse for pure services. Because production and consumption are synchronized, consumers exert an influence on the production of a pure service. The assessment of its quality depends on both subjective and objective factors of both the providers of the service and its consumers. But service quality is highly subjective, and varies from Consumer to consumer, Factors include the quality of the environment when co service is provided, the conditions of the facilities, the appearance and well-rounded background of service providers, and their willingness to serve consumers.

As a result, the most important difference between pure labor and non-pure labor is that consumers have the opportunity to participate in the pure service process. A prime example is education. As a Chinese saying goes, Teaching students in accordance with their aptitude.” In other words, there is no bad student, but there are bad teachers.

The use value and value of services

It is generally accepted that the value of a material product has a dual character. If it is a commodity, it has use value and value. The first refers to its usefulness, and determines what kind of object is functioning as a commodity. If it has no use, it ceases to be a commodity. This makes the commodity itself a use value. As Marx once argued, a commodity, in the first place, is an object independent of a subject, which is capable of meeting people’s needs.

A commodity is, in the first place, an object outside us, a thing that by its properties satisfies human wants of some sort or another. The nature of such wants, whether, for instance, they spring from the stomach or from fancy, makes no difference …. The utility of a thing makes it a use value. (Marx 1965, p. 27)

Although Marx’s comment concerns material production, it has important implications for our understanding of the nature of service labor. As we have noted, for Marx a service only expresses a peculiar use value of labor. Therefore, we argue, service also possesses the attribute of use value. However, a service is not useful as a material object but as living labor. Its nature lies in the process that supplies it, in contrast to the use value of an immaterial object.

A service must have some use value, just like a material product. This fact presents itself as follows:

It meets people’s material and spiritual needs. Business establishments produce both material products like grain and autos, and immaterial products like transport and education. Both are indispensable for the normal running of a society, and both have use value. Under certain circumstances, they are mutually substitutable.

The use values of services are part of social wealth. In capitalist society, social wealth is exhibited as an accumulation of products. However, as it develops, the proportion of services in output rises steadily and becomes more diverse. New services become available and existing ones improve, significantly increasing the use values at society’s disposal.

Under the socialist market economy, services are bearers of exchange value, just as material products are. A service per se, a process in which living labor is the input, is actually a kind of activity, notwithstanding it cannot be turned into a material object.

Services, if provided as commodities, also have value. This is because:

Under the socialist market economy, there are different productive entities which are independent producers within the social division of labor. To convert individual labor into a part of social labor, it has to go to the market to enter the exchange process.

When an individual manufacturer produces a service, it consumes human labor in a general sense, just as human labor is consumed when manufacturing a product. The two types of labor are both general human labor.

Each type of service has a different use value. Though they consume different concrete human labor, these different use values, by entering ex-change, finally turn into social values. Therefore, the source of their value is none other than abstract human labor, which forms their value. Abstract human labor is thus the essential characteristic of their value.

So how can we determine the amount of the value of a service? For a material product this is measured by the amount of labor required to produce it. But as noted earlier, the synchronicity of the production and consumption of service labor suggests that to a large extent, consumers participate in service production. As a result, the quality of the service becomes important, distinguishing it from material product production, The creation of value in service depends on both the service provider and consumer.

Therefore, the socially necessary labor time of a productive service is the average level of labor time a service provider needs in order to produce it This comprises the following;

Constant capital, being the value of materials consumed in service pro-duction. This creates no new value but is transferred to the service product by the living labor of the service producers.

Variable capital, being the value of labor the service laborer contributes.

Laborers perform two functions: they compensate for the lost value of constant capital consumed in production, and create new value which exceeds the value they consume in reproducing their labor power.

Surplus value is created by this surplus labor and appropriated by the capitalist.

Three misunderstandings about value creation by service labor

Service is a type of immaterial product. It is widely believed that because a service is intangible, it cannot be presented to consumers in materialized form. It is therefore supposed that “being immaterial” is the defining characteristic of a service. But actually, this distinction is coterminous with Adam Smiths concept of productive labor. We argue instead that “being immaterial” is a necessary but not sufficient condition for being a service. What is essential about a service is that it should be useful only as living labor. This is the central premise of our own distinction between material products and services.

For example, if a software company posts a product on the internet for customers to download, is this a material product or a service? This question admits of different answers. If we hold fast to the notion of “immaterial product” then the software company sells a type of service, since its product is intangible. But if the usefulness of service labor is taken to be the defining characteristic of a service, then the downloadable product is a real product, not a service. But if the software company provides its customers with technical consulting, this is a service.

The second misconception concerns whether service labor creates value. In fact, not all service labor creates value. Two schools of thought are in play. The first argues that only those services that are aimed at producing material products create value. Pure services then do not create value, and nerdy realize or distribute value. The second school believes that all types of labor create value, not only in material goods production but in cultural production. From this standpoint even governmental agencies, the military, and the police system may create value. We consider both viewpoints to be one-sided. Not all service labor creates value; the services provided by the military and governmental agencies do not create value. But pure service that provides a use to private consumers or business creates value, whether or not it leads to a material product.

Services contradicting the law of a society or social morality do not create value. In any society, there are organizations whose services contradict law and social morality, on which the authorities should crack down hard. Since China practices a system of socialist market economy, it should outlaw any service contradicting its law and social morality. For example, theft does not create value (even when organized as a business with constant capital such as firearms.

Studies of labor productivity in the service industries

In the early years of human society, human beings lacked means of production; all forms of labor were a test of material human strength. With the accumulation of productive experience and means of production, the efficiency of labor has risen, helping to liberate human beings from the shackles of manual labor. With the advent of capitalism, advances in S&T further upgraded the means of production, and released energy to expand production massively. The capitalist economies thus could create and accumulate more social wealth in less than 100 years than in any previous period in history.

Managing production on an appropriate scale, in the case of material products, involves subdividing them into basic units, with each basic unit homogeneous in terms of use value. Subdivision is the basis of statistical analysis and hence management. The value of each basic unit can however be aggregated with that of another, as in measuring the output of a broad sector.

Things are in general different in the service industries. Since a service Is a process of living labor input, it is futile to try to subdivide living labor. Consequently, aggregation is impossible and as a result, a basic condition for management of service production on an appropriate scale is not satisfied.

Nevertheless, with the development of S&I some service industries, characterized by a low level of individuality, do use modern technology to provide subdivided packages of service whose values can be aggregated. Thus, the transport and telecommunication industries can be managed on an appropriate scale.

The mode of production of each of the many service industries varies, so that some provide standardized services while others do not. In consequence, the composition of their capital structure also varies. Standardized services make it easier to replace manual labor with advanced means of production (for example, machines), making it more likely that their industries will become capital-intensive service industries in which labor productivity is rising.

However, in less standardized service industries, because of their high level of individualization, production by its nature is not possible in the absence of consumers, making it more difficult to replace manual labor with machines. In consequence, it may be harder to raise labor productivity. A prime example is the medical profession. Although modern medical technologies help with diagnosis, the diagnostic process itself cannot continue in the absence of patients.

These differences between service and material production create theoretical obstacles to measuring the output of the service industries, and consequently, increases in labor productivity. We now turn to this issue.

Western studies

One of the findings of Western economic and statistical studies is that the rate of productivity increase in services has been lower than in manufacturing. Yet the percentage of services in output has been increasing steadily. The end result is a tendency for the overall growth rate of productivity in the Western economies to slow down.

Fuchs (1968, 1987) was the earliest economist to raise the issue of service productivity, arguing that it was one of the main reasons for rising employment in the service industries. He made three points. First, since the income elasticity of service demand is greater than 1, the share of services in output will grow with income. Second, the externalization of services is developing. Improved technology and rising incomes lead households and businesses to seek services from the market instead of providing them. Last but not least, the relatively low productivity of services makes their average cost higher than elsewhere.

Research on labor productivity in the service industries helps explain a puzzle. In theory we have shown it is hard to raise labor productivity in industries providing non-standardized services. But empirically, there is throng evidence that such a phenomenon exists. So we introduced the human capital variable, and found that the growth of labor productivity is positively related to its growth rate and output elasticity.

We cannot however rule out of court the idea that labor productivity grows rather slowly in the service industries, because the sector as a whole is a mix of labor and capital-intensive industries, and includes many knowledge-based service industries. Policy makers need a more precise understanding of how the service industries are developing, fostering the education and training sectors to increase the human capital of laborers and promote the development of knowledge-based service industries. This would improve the labor productivity of the service industries and allow the service industries to create more social wealth.

Empirical studies on how value is created in service industries

The path of economic development of every country suggests that service industries are assuming a more and more important role in its economic landscape, especially in the 21s century. Generally speaking, they employ the largest number of laborers and their output takes up the largest percentage of a country’s GDP. It is not surprising that they are increasingly believed to be the mainstay of a modern national economy.

Taking the USA as an example, we found that 75% of its GNP was produced by the service sector, and 76% of US laborers were employed in service industries. Considering this prominent position, this is clearly an area of scholarship that deserves in-depth study. As the importance of the service industries rises, it is imperative to clarify the issues concerning value creation by labor in these industries, and we therefore undertook empirical stud-is to shed light on this.

The service sector is composed of a large number of organizations, and contains both capital and labor-intensive industries. In the initial stage of industrialization of a country, most service industries are labor- intensive, and capital-intensive industries are few and far between.

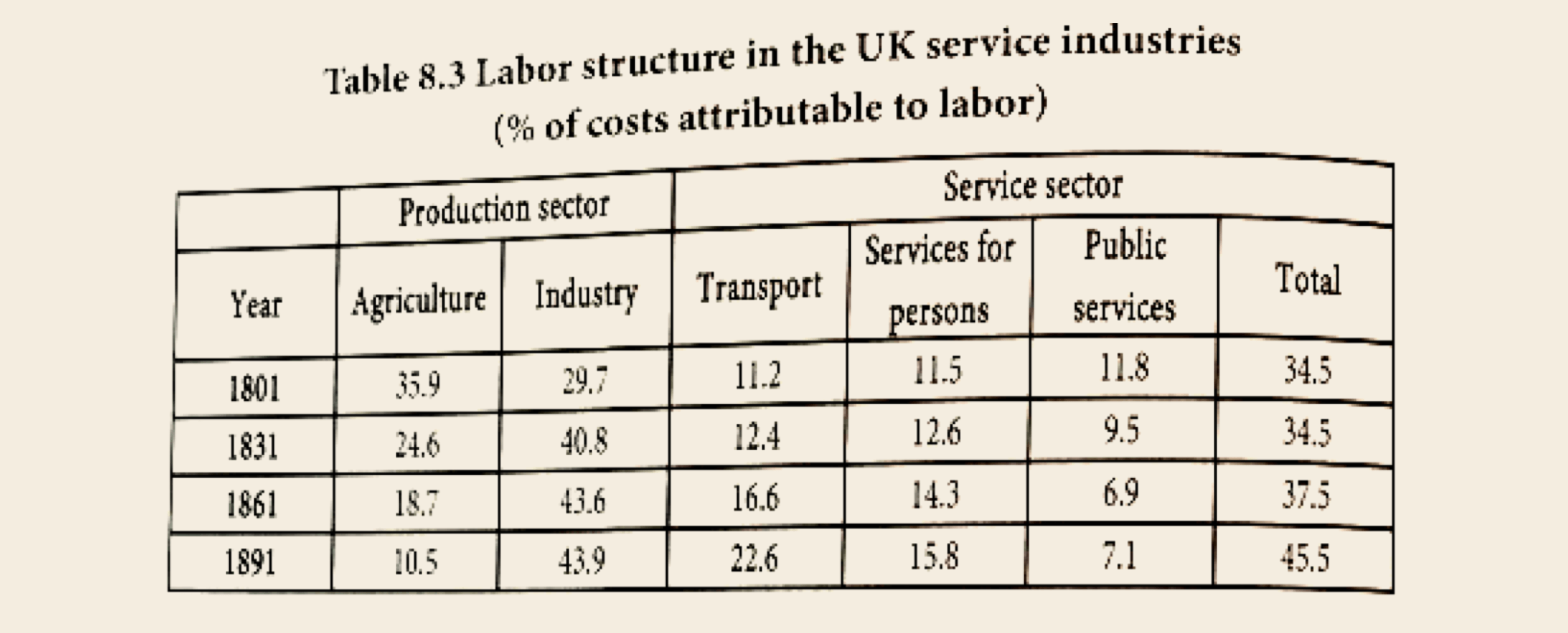

The authors attempted to illustrate this point by citing the structure of British labor power. Based on Table 8.3, we found that the service sector for persons took up a greater percentage of the entire sector over time. This suggests that the British service sector was basically labor-intensity-oriented in its early years.

The preceding arguments underline how important it is to study both the theoretical analysis of service industries and their empirical development. In the early stages of industrialization, most service industries are labor-intensive, a point illustrated by a glance at the British labor force statistics, shown in Table 8.3. Services to persons took up a greater percentage of the labor force in the 19th century, and it was only in the post-industrial age that the capital-intensive service industries started to blossom. Even so, some labor-intensive service industries remain.

We chose labor costs in the service industries as an indicator instead of labor time input, because data on the latter are hard to obtain.

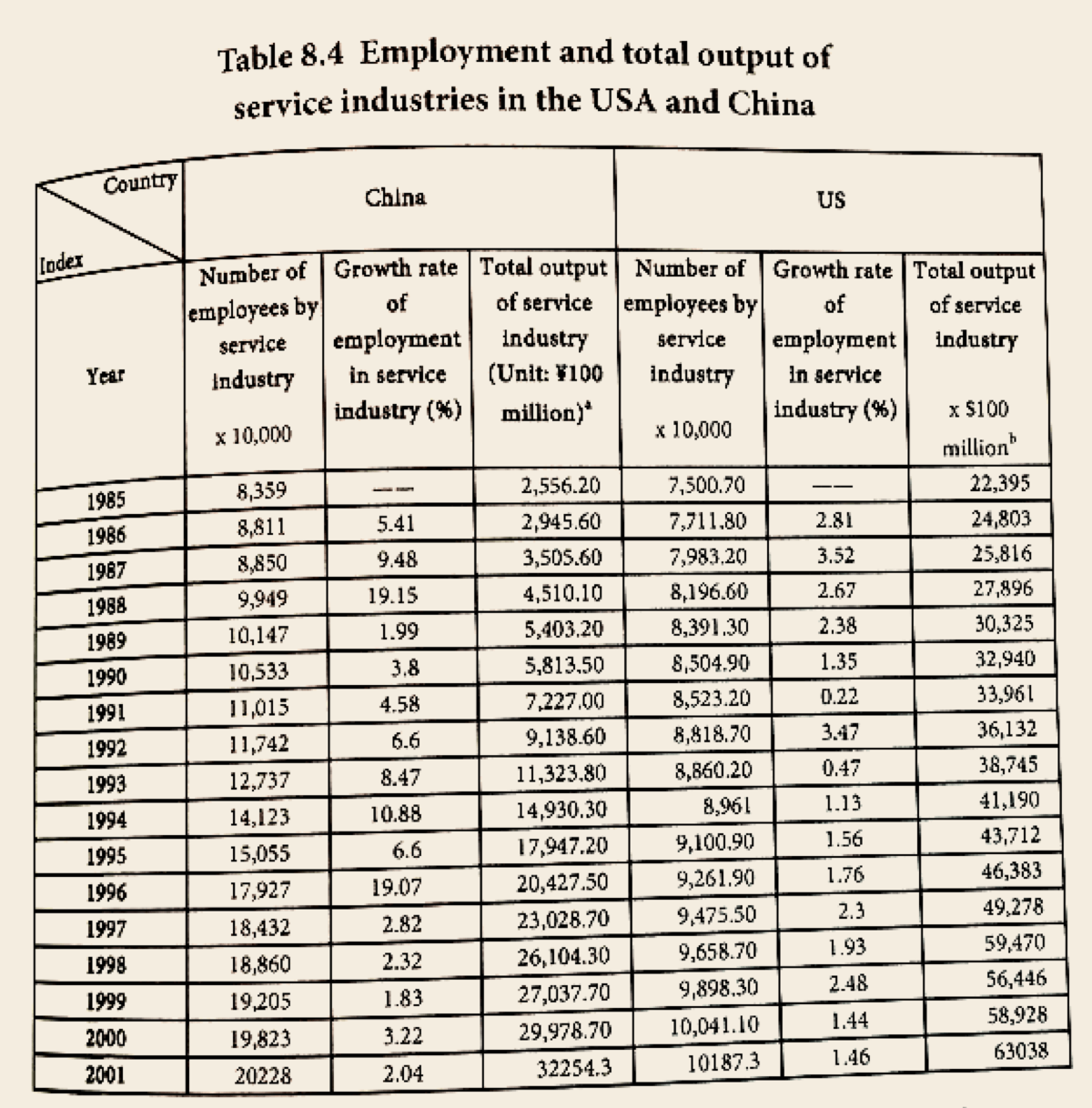

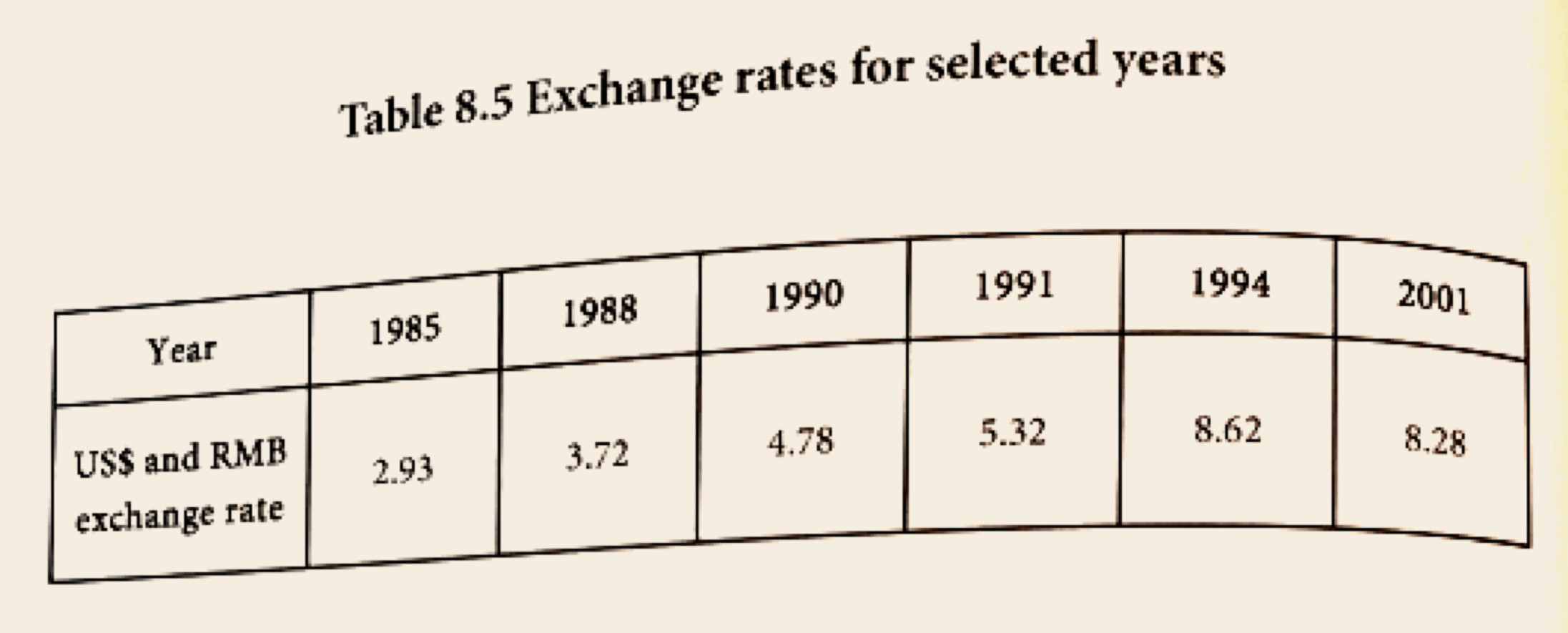

We now present a detailed contemporary empirical study, composed of two parts. The first is a comparative study of value creation by labor in the US and Chinese service industries. Since the USA is a well-developed market economy, human capital is more concentrated in its service industries than in China. If human capital increases earnings, we should expect the value added per worker in US service industries to be higher than in China.

The second part is a comparative study of the structure of US and Chinese service industries. Its purpose is how labor inputs affect value creation se sch industry, and bring to light the law of the development of developed. country services, hopefully providing meaningful information for China’s policy makers.

The regression model

Certain factors dominate the path of economic development even though each factor plays a different role. We focus on the relationship over time between the output of the service, industries, which we shall call Y, and the number of laborers employed there, which we shall call X. This can be represented as a linear function, for simplicity. If more factors are taken into consideration, the analysis gets more difficult. Our simple model singles out the main factors that impact the development of service industries, using a one-dimensional linear regression equation to test our hypotheses. The sampling frame for China and the USA was between 1985 and 2001.

We represent the relation by the equation:

Y= a + bX (Equation 8.1)

China

For China’s service industry, equation 8.1 can be estimated as:

Y = -17,904.36 + 2.331X (Equation 8.2)

(-14.138) (6.658)

R2 = 0.989

R = 0.990

F = 710.634

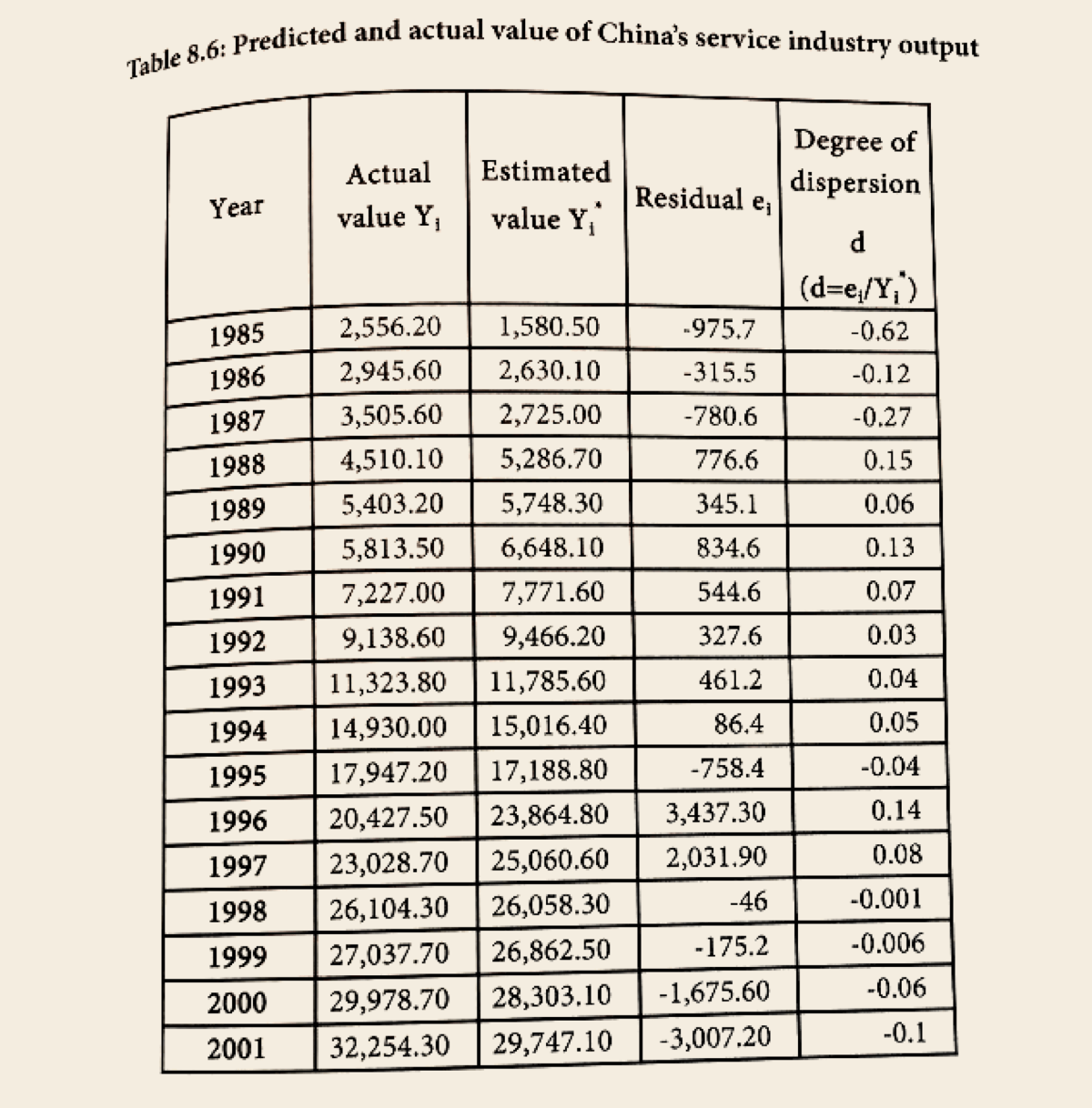

Table 8.6 shows the residuals of this regression.

The equation thus explains 98.9% of the total variance of the sample. The t-test value ta0 is -14.138 and ta1 is 26.658. showing the results to be statistically significant with a p-value below .05. The degrees of freedom are 1 and 15, respectively. The F-distribution is F0.05 (1,15) 4.54, and is also valid. The results thus suggest that the number of people employed by China’s service industry explains most of the variation in its total output. The relation is positive.

U.S.A.

Y=-98516.57 +15.623X

(-19.22) (27.19)

R2 = 0.98;

R = 0.99;

F = 739.28

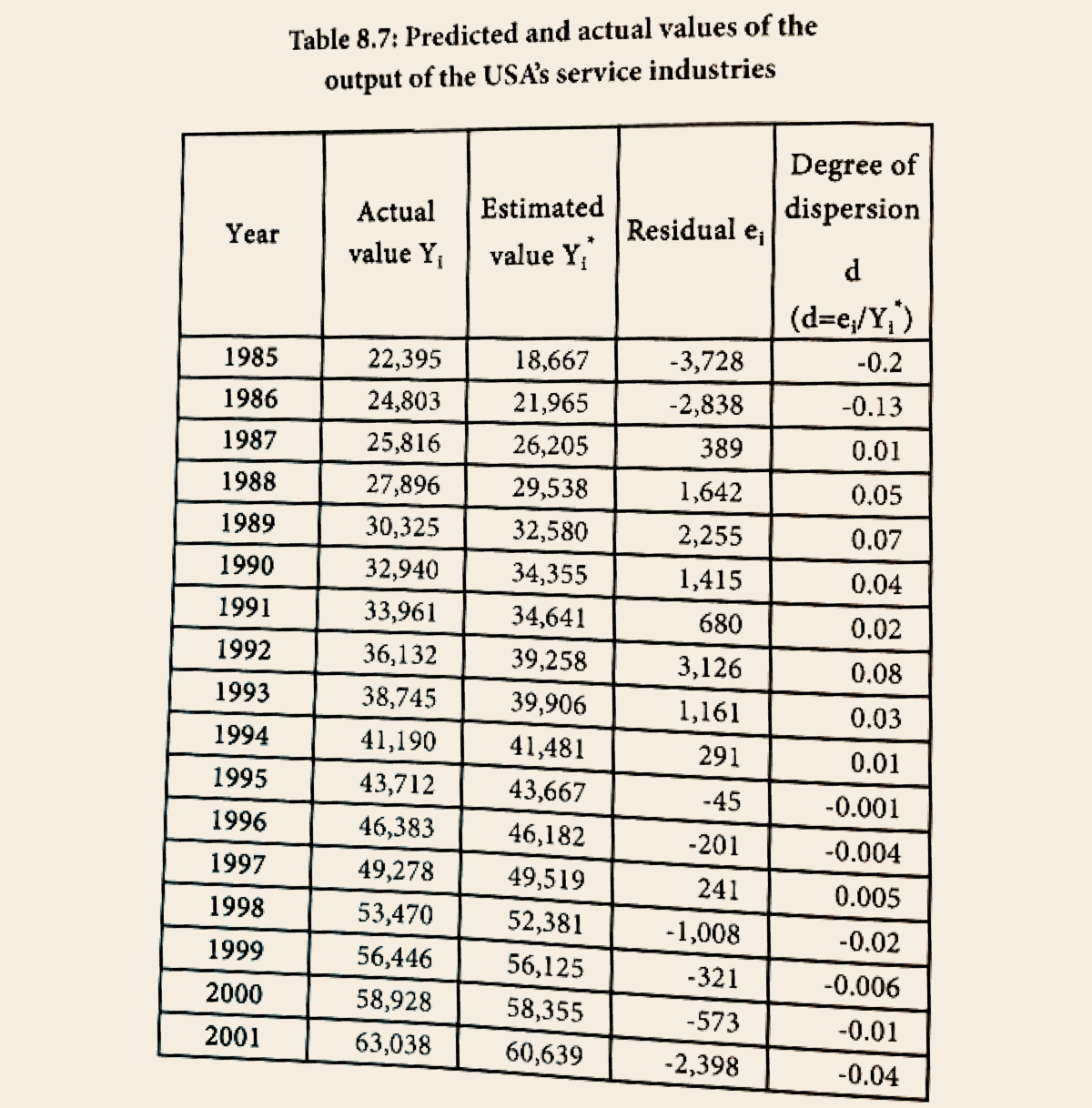

The residuals are presented in Table 8.7.

This result is equally significant. Employment explains 98% of total variance, with a correlation coefficient of 0.99. ta0 is -19.22 and ta1 is 27.18, yielding a p-value also below 0.05. The degrees of freedom are 1 and 15, respectively.

Comments

The independent variable in the Chinese regression has greater explanatory power than in the US regression, reflected in the variance explained by the independent variables of each regression model. This might suggest that the proportion of the increase in China’s output of service industries owes more to the increase in the number of people employed by this particular industry than in the USA: that is, labor intensity plays a greater role in the development of China’s service industry than the human capital factor.

However, the dispersion in the Chinese regression is greater than in the American regression, which suggests the number of laborers may have less impact on output in the USA. As previous chapters have shown, for example the export rankings of specialized services such as accounting and technology, and also audiovisual products, suggest that US service industries are generally human capital-intensive.

Employment in China’s service industries has grown continuously since 1985 at an average rate of 5.7% annually, absorbing an increasing number of laborers. The sector has become an important component of China’s economy, creating large amounts of value. In contrast, the US service industries are well developed. Although output is increasing, employment is growing more slowly, at an average annual rate of 2%. This suggests that most US service organizations have transformed into knowledge-based service organizations; their value-creating capacity depends on the human capital factor rather than the sheer number of laborers. This confirms Marx’s argument that complex labor is an aggregate of simple labor.

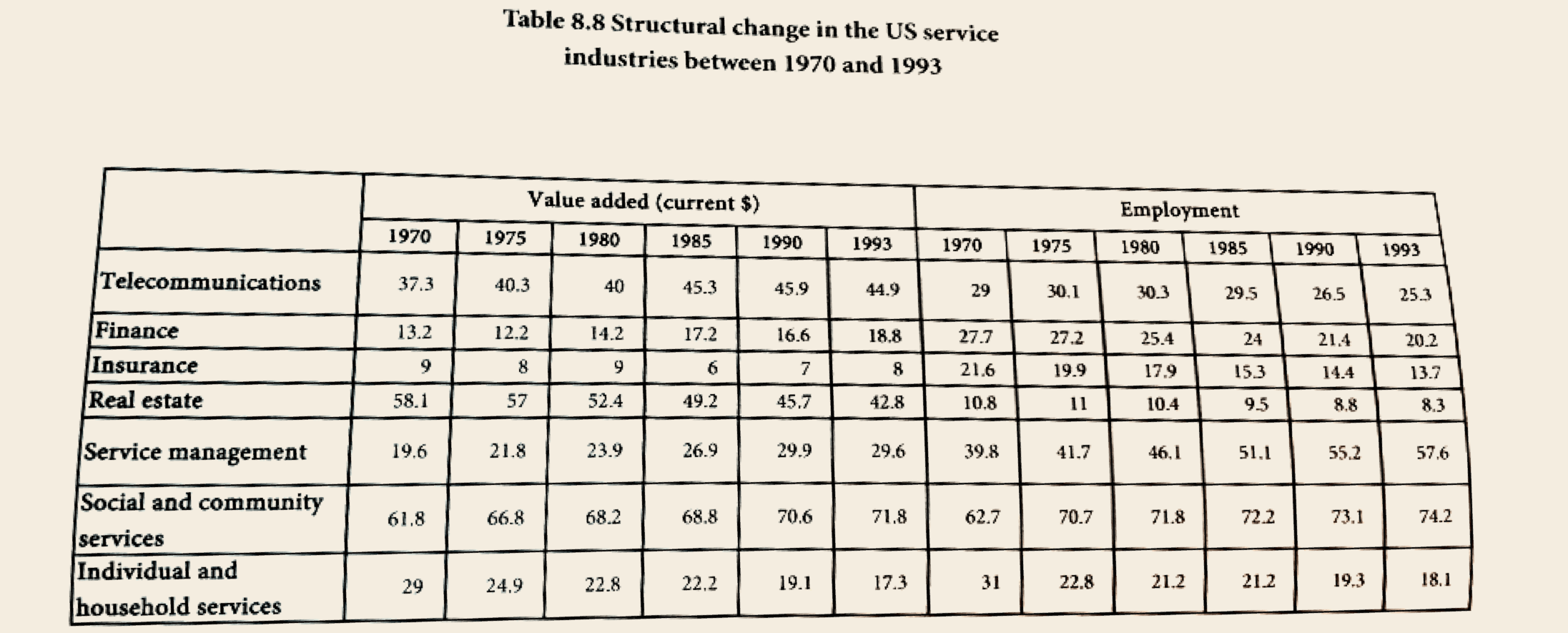

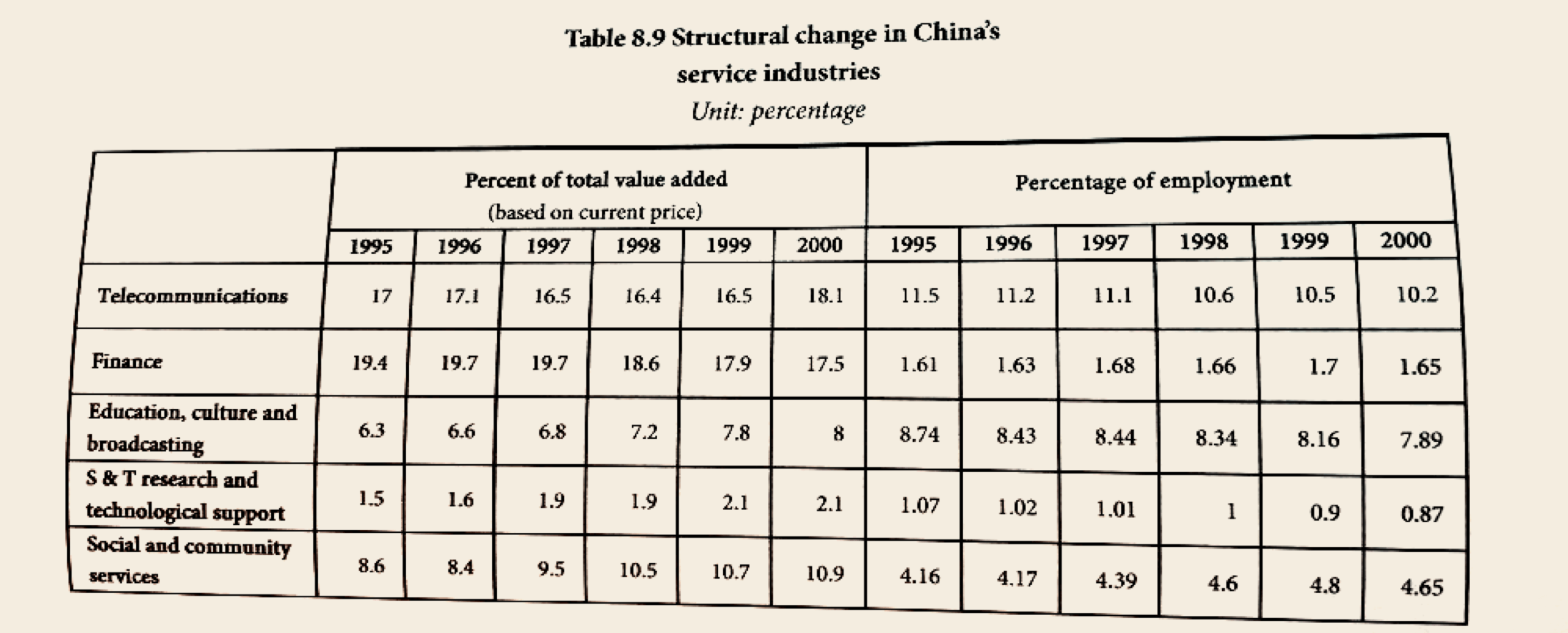

We now move on to explore these issues from the standpoint of the service industries’ internal structure. Tables 8.8 and 8.9 present data on the structural evolution of the US and Chinese service industries respectively. In these tables, each figure is a percentage of the total in the relevant major Category. Thus, the figure for telecommunications in China in 1993 tells us it accounted for 41,9% of its general type of service industry, which was transport, telecommunications and storage systems, etc.

Table 8.8 shows that the internal structure of the US service sector changed significantly in the two decades to 1993. Telecommunications grew from 37.3% of the secondary service sector in 1970 to 44.9% in 1993, an annual change of nearly 8%. However, growth reached a plateau in the 1990s, and the number of people employed by this industry then started to decline. This trend supports the hypothesis that telecommunications and transport share similar characteristics, having a greater potential to improve labor productivity through technological progress. It further supports the argument that although the human capital factor is in the ascendant, it may still create greater value than before with fewer laborers.

The second important change is that the total output of management and social services such as educational and medical services has risen continuously, at annual rates as high as 10%. The number of people employed by these industries is also increasing. This suggests that those service industries that provide individualized services for the public will inevitably suffer a slower rate of growth in labor productivity. Most of the increments in value added come from the increasing number of people employed in these service industries.

The third important change is that the output and the number of people employed by the insurance industry and real estate was declining. This suggests that the decreasing transaction costs of these industries may benefit the overall economy.

Finally, the percentage of value added compared with output in personal and household services, as well as the number of people employed by these industries, saw a significant decline. This suggests that these services are increasingly being replaced by other commodities, and run the risk of being eliminated eventually.

Table 8.9 illustrates the equally important changes under way in China’s service industries. As China’s economy grew, its most important basic industry – telecommunications – was developing more rapidly. By 2000, its value added accounted for 18.1% of the corresponding service sector, an annual growth of 1.3% since 1995. More importantly, these industries create large amounts of value for the whole society, while the number of people they employed gradually declined. This trend is consistent with that of the USA, and suggests that under the influence of modern technologies, the transport and communications industries are very likely to increase their use of human capital and consequently create more value with less labor input. Employment in the finance and social service industries was steady, while the number of service industries providing miscellaneous services was rising. This suggests that as society develops, the service industries are becoming more externalized.

Employment in education, culture, and broadcasting, as well in S&T industries, continued to decline while their value added grew, suggesting they were making more intensive use of human capital.

The similarities between the structure of Chinese and US service industries are thus that the transport industry is developing rapidly while employment declines relatively, while transaction-based service industries like finance are declining. The difference is that the value added by China’s service sector is growing much more rapidly. The service demands of business establishments have been rising rapidly while the number of laborers employed by China’s education and S&T industries is declining. This suggests the decline of laborers in human capital intensive industries makes value creation more difficult.

This article was an excerpted chapter from ‘The Creation of Value by Living Labour: A Normative and Emperical Study‘ by Cheng Enfu, Wang Guijin, and Zhu Kui. Photo from Pexels.com.