In our culture, the language of “survival” is ubiquitous. From climate change and nuclear war to the liberatory struggles of oppressed peoples and the COVID-19 pandemic, the refrain from the discourse is how to survive, rather than thrive, in our current conditions. As Andrew Keshner wrote for MarketWatch in January of 2021, 38% of Americans see themselves in “survival mode,” or “focus[ing] on the day-to-day” rather than any planning for the long-term. This is not without reason. As an increasingly limited political and economic atmosphere provides little to no real avenues of change, people turn into themselves and seek only to withstand the worst of our system. There’s little space for personal or social betterment.

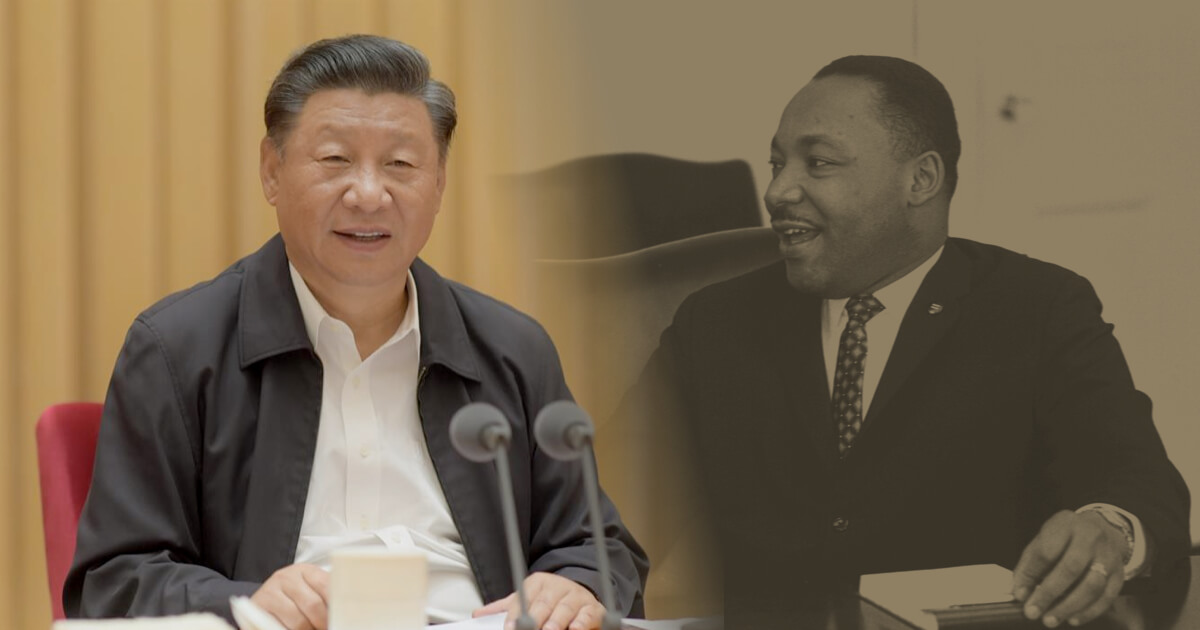

How did we get into this mess, and how do we get out? Interestingly, prescient answers to these questions were provided nearly four decades ago by one of America’s most astute historians and cultural critics: the late Christopher Lasch. The former Watson Professor of History at the University of Rochester, Lasch is best remembered for his path-breaking book, The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations (1979). In this work, Lasch correctly diagnoses the issue of American life— that the “cultural turn” in American social existence, with its accompanying abandonment of material politics and increasing role for technocracy, has created a generation of narcissists with little to no regard for any overarching political paradigm beyond self expression.

Unfortunately, Lasch has been perennially misunderstood. The narcissism he describes in his works is less akin to the modern colloquial sense in which we apply it— someone who is self-obsessed and sociopathic— but closer to psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud’s original use of the term. Narcissism, to Freud (and Lasch), represents someone who cannot differentiate themselves from the rest of the world, and therefore cannot identify with anything outside of themselves. Any attempt to find meaning in actions that exist to improve the social life of others or the world that we inhabit falls on deaf ears, and politics becomes more and more an exercise in personal branding and self aggrandizement. As such, Lasch calls on us not to abandon our sense of self, but rather to abandon a selfhood that negates our sense of community, sociality, and moral purpose. Additionally, due to his emphasis on the aforementioned values, Lasch has been misread as a cultural conservative who rejected the radical liberation movements of the 1960s. This couldn’t be further from the truth. In fact, Lasch was a socialist and Marxist whose critique of modern liberalism’s failings called for a more radical, democratic politics.

The late Christopher Lasch. Former Watson Professor of History at the University of Rochester, Lasch is best remembered for his path-breaking book, The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations.

To clear up these misunderstandings, Lasch wrote a sequel to The Culture of Narcissism that expands and clarifies his ideas. This book, The Minimal Self: Psychic Survival in Troubled Times (1984), anticipated our culture of survival by decades, meticulously laying out how and why our culture has devolved the way it has. When survival is the only watchword of our lives, it becomes increasingly difficult to think of ourselves as agents of social transformation. As Lasch wrote in the preface, “under siege, the self contracts to a defensive core, armed against adversity.” This “defensive core” is the basis for narcissism, which he defined as “seek[ing] both self-sufficiency and self-annihilation: opposite aspects of the same archaic experience of oneness with the world.” Narcissism, to Lasch, was a poor replacement for a real experience of selfhood. “Selfhood is the painful awareness,” he wrote, “of the tension between our unlimited aspirations and our limited understanding, between our original intimations of immortality and our fallen state, between oneness and separation.” A meaningful and positive understanding of the self, both individually and socially, resides in a dialectical relationship between our bounded material existence and our unbounded subjective experience.

Our collective reverse transfiguration of selfhood into a monstrous narcissism stems from, according to Lasch, the influence of mass culture. However, he was quick to point out that this narcissism was not simply an egoism brought about by an outsized consumer market. The markets themselves, echoing Marx’s notion of “commodity fetishism,” mold consumers into “see[ing] the world as a mirror, more particularly as a projection of one’s own fears and desires.” Instead of this consumer mirroring emboldening us as individuals, it makes us “weak and dependent.” In this way, our everyday experiences with consumer goods, from toothpaste to televisions, negate our sense of positive selfhood, of acknowledging our relationship to others and the world. It also stunts political aspirations, as politicians and public policy become increasingly a consumer choice and not a vehicle for transformational change. Lasch believed that this arrangement “make choice the test of moral and political freedom and then reduce[s] it to nonsense.” In a very real sense, Lasch anticipated the “culture wars” of the last forty years, which boil political actors down to commodified “selves” that reflect the consumer choices of a particular cultural milieu, thus reinforcing the entrenched economic and political interests of the ruling class.

Alongside the consumer mentality is the survivalist ethic, one rooted in what Lasch called the “trivialization of crisis.” In his time, the United States and much of the developing world was facing a myriad of crises, mostly brought on by the breakdown of the post-WWII economic order. The rise of inflation, fuel shortages, and economic stagnation plagued the populace— underscoring how crisis pervaded every aspect of life. The environmental and nuclear disarmament movements also used the language of permanent crisis to articulate the importance of survival, above all else. Yet, as Lasch pithily recognized, the emphasis on the centrality of survival trivializes crisis itself, and as such provides most people with little incentive to join a cause. If survival is the only thing that matters, then you really can’t motivate people to care, or worse, they become completely insular and reactionary. As Lasch wrote, “those who base the case for conservation and peace on survival not only appeal to a debased system of values, they defeat their own purpose.” Our movements to fight climate change and establish peace, among many others, must articulate a vision beyond mere survival and cultivate a positive, optimistic outlook of the future. Only then will it become a movement with real lasting power.

Another way in which our culture trivializes crisis and survival, in Lasch’s estimation, was the way we talk about the Holocaust. He was increasingly concerned with how mass media culture and even scientific discourse analyzed the horrific event, finding “lessons” from survivors on how to cope with common adversities. As he wrote:

This exploitation of the ‘Holocaust’ can be charted in the growing preoccupation with survival strategies, in the recklessness with which commentators began to generalize from the concentration camps to normal everyday life, and in their increasing eagerness to see the camps as a metaphor for modern society.

Instead of seeing the Holocaust as what it was, an event of extreme barbarism and inhumanity that shaped those who endured it, it is seen merely as another example of how to overcome challenges in one’s life. In attempting to paint society as a concentration camp, Lasch argued, these modern analysts of the Holocaust undermine the historical realities of the era while simultaneously belittling the real trauma and pain that survivors and those killed faced. “When Auschwitz became a social myth, a metaphor for modern life” he noted, “people lost sight of the only lesson it could possibly offer: that it offers, in itself, no lessons.” What he’s getting at here is that we debase the legacy of the Holocaust by turning it into a one more lens to understand the struggles of our everyday existence, rather than as a century-defining crime that often blunts analysis by its cruelty, sadism, and inhumanity.

Lasch was also critical of the emerging “New Age” movement of his time, a spirituality movement that he believed reinforced narcissism. Traditional religions, in his estimation, “have always emphasized the obstacles to salvation,” while “modern cults . . . promise immediate relief from the burden of selfhood.” A healthy selfhood seeks to “reconcile the ego and its environment”; the New Age movement, by contrast, “den[ies] the very distinction between them,” and thus cements in a person a stultifying narcissism. While it is certainly true that modern manifestations of traditional religions can have narcissistic effects, specifically the American evangelical movement and its obsession with riches and self-fulfillment, Lasch was nonetheless on to something here. New Age beliefs, from Rhonda Byre’s The Secret to Tony Robbins’ Awaken the Giant Within, reject social understandings of self-transformation and embrace an all-too-pervasive cult of the self. This limits our capacity for empathy, companionship, and collective action. It is no wonder that in our age of Neoliberalism, with its own cult of individualism, finds a complement in these types of beliefs.

In homing back in on the nature of narcissism, Lasch laid out a perfect illustration of what he’s trying to articulate in his work. He retells the myth of Narcissus, who drowns himself trying to connect to his own reflection— a visage he doesn’t even recognize as a reflection. As Lasch so perfectly noted, “the point of the story is not that Narcissus falls in love with himself, but, since he fails to recognize his own reflection, that he lacks any conception of the difference between himself and his surroundings.” This is the crux of the matter; narcissism isn’t just a cheap formulation of “self obsession,” but a person’s total inability to distinguish between themselves and the world. As such, they fail to grasp how others live, societies function, and even a healthy conceptualization of inner life. This is what the hyper-atomized, consumerist culture we live in does to us. It destroys our conception of selfhood and replaces it with a reflection that, much like Narcissus, will undermine our very ability to live well and fight for others. In other words, Neoliberal capitalism made narcissists of us all.

This has profound implications for our politics. Lasch outlined in the last two chapters of The Minimal Self how these changes reorient our political situation into three major groups: the “Party of the Superego,” the “Party of the Ego,” and the most challenging to describe, the “Party of Narcissus.”

The Party of the Superego most deftly describes the emerging neoconversative movement, who to Lasch were “former liberals dismayed by the moral anarchy of the sixties and seventies and newly respectful of the values of order and discipline.” Moral regulation is of paramount importance to this group, seeing it as a panacea to all of our political and cultural woes. As Lasch pointed out, they stand “for a morality so deeply internalized, based on respect for the commanding moral presence of parents, teachers, preachers, and magistrates, that it no longer depends on the fear of punishments or hope of rewards.”However, this outlook “overestimates the superego” for Lasch, who rightly acknowledged that fear is a powerful motivator of moral actions. In its “condemnation of the ego,” the rational component of our psyches, the Party of the Superego “breeds a spirit of sullen resentment and insubordination.” The Party of the Superego fails to provide the material and social conditions for moral conduct to take place, which would inspire in people “confidence, respect, and admiration.” In the void of material needs, the Party of the Superego forces moral regulation through fear. If there is any indication that this is true, review how conservatism these days asks so much of the people it seeks to govern without actually addressing people’s actual needs, like housing, healthcare, and higher wages. This formula for social change will collapse under the weight of its own contradictions.

However, modern liberalism, what Lasch calls the Party of the Ego, isn’t that much better. It takes the opposite approach, foregrounding human reason and science and its solutions to political quandaries. Instead of improving our politics through moral regulation, it seeks what Lasch referred to as the “therapeutic approach,” using developments in psychology as a means to ameliorate human suffering and social unrest. Similar to the Party of the Superego, the Party of the Ego overestimates the efficacy of this method, thereby turning our politics away from democratic participation to technocratic domination. “The therapeutic morality associated with twentieth century liberalism,” Lasch contended, “destroys the idea of moral responsibility, in which it originates, and that it culminates, moreover, in the monopolization of knowledge and power by experts.” It fetishizes the sciences, turning them away from the application of human reason to solve our problems and understanding the world into a cult of expertise that undermines the democratic process. This is also true in our time; liberal politicians and policy makers hail “we believe in science” as a cultural shibboleth while simultaneously supporting harmful policies that go against current scientific knowledge, like approving new oil drilling permits as climate change ravages the planet or providing a few measly COVID-19 tests as the illness rips through the populace. The Party of the Ego really isn’t all that interested in the scientific process— it only seeks to use science’s cultural cachet to influence voters. But like with the Party of the Superego, the Party of the Ego’s contradictions doom its program.

Finally, we get to the Party of Narcissus, the supposed third option that emerged out of political malaise of the aforementioned two camps. This term most exemplifies the “New Left,” a loose ideological consortium of socialists, anarchists, and other left-wing political actors that emerged during the 1960s who embraced the politics of the personal and minimized the importance of class struggle. This group either implicitly or explicitly abandoned the “Old Left’s” commitment to Marxism in exchange for a politics rooted in personal experience. Lasch was mixed on this group’s political potential, noting its strengths of democratic participation, critique of power, and distrust of organizations while acknowledging the weaknesses of embracing an all-encompassing politics of cultural revolution. Specifically, Lasch was concerned about its tendency to overstate the case against industrial technology and the self, noting that a transformational politics “rest[s] on a respect for nature, not on a mystical adoration of nature. It has to rest on a firm conception of selfhood, not on the belief that the ‘separate self is an illusion’.” Limiting one’s political horizon to the manifestations of feelings or a retreat from science and material analysis will only be co-opted by the existing power structure. If you need any indication this is true, think of how mainstream political discourse is almost exclusively cultural, with liberals and conservatives defending their hyper-personalized, commodified political identities while ignoring material issues of poverty, wage stagnation, homelessness, hunger, and health care.

So, if all three of these paradigms are faulty, what should be our path forward? In this respect, Lasch was much better at explaining our problems than our solutions. He offered a return to “practical reason,” or “phronesis,” a concept associated with Aristotle that “describes the development of character, moral perfection of life, and the virtues specific to various forms of activity.” Modern politics’ failures, in Lasch’s estimation, stemmed from the elevation of “instrumental reason,” a concept usually associated with the Enlightenment that sees the development of science and technology as goods in and of themselves, divorced from any ancillary moral implications. A superb cultural example of this dilemma comes from Dr. Ian Malcolm (played by Jeff Goldblum) in the classic film, Jurassic Park. In discussing the implications of bringing dinosaurs back from extinction with the park’s founder, Dr. John Hammond (played by Sir Richard Attenborough), Dr. Malcolm says “your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should.” In thinking only of scientific ends, the park’s designers and scientists unleashed a biotechnological horror on humanity. When we divorce moral considerations from our technological societies, we will create a wasteland of consumer-driven narcissism that feeds on the very immorality it creates.

Instead of mere instrumental reason, Lasch advocated for a politics where “the choice of means has to be governed by their conformity to standards of excellence designed to extend human capacities for self-understanding and self-mastery.” In other words, organizing society with deliberate moral aims at the outset. This can be achieved only when we acknowledge a healthy understanding of the self, which is rooted in “the critical awareness of man’s divided nature. Selfhood expresses itself in the form of a guilty conscience, the painful awareness of the gulf between human aspirations and human limitations.” Human beings are a product of material conditions, and we ignore these conditions at our peril. Lasch believed, despite its own shortcomings, a blending of moral purpose, technological development, and a communitarian spirit is the only path that might work.

There are certainly limitations to this approach. Lasch lauded the virtues of the “Judeo-Christian” ethic of individualism but doesn’t interrogate the problematic features of its application, specifically imperialism, colonialism, and misogyny. He also ignored the politics of class struggle, something that all successful revolutions of the working class place at the forefront of their movements. Nevertheless, Christopher Lasch’s The Minimal Self is an important, if overlooked, work in the canon of his thought; it articulated more directly his concerns and offered a clearer alternative than his more celebrated work. His crusade to stem the tide of narcissism and politics as cultural affect is something to be celebrated, for he anticipated so much of what came to pass. Our age is also one of crisis and survival, and if we seek to get beyond its confines, Lasch’s ideas represent part of the blueprint to change our collective future.

Re-published where permission from Midwestern Marx.