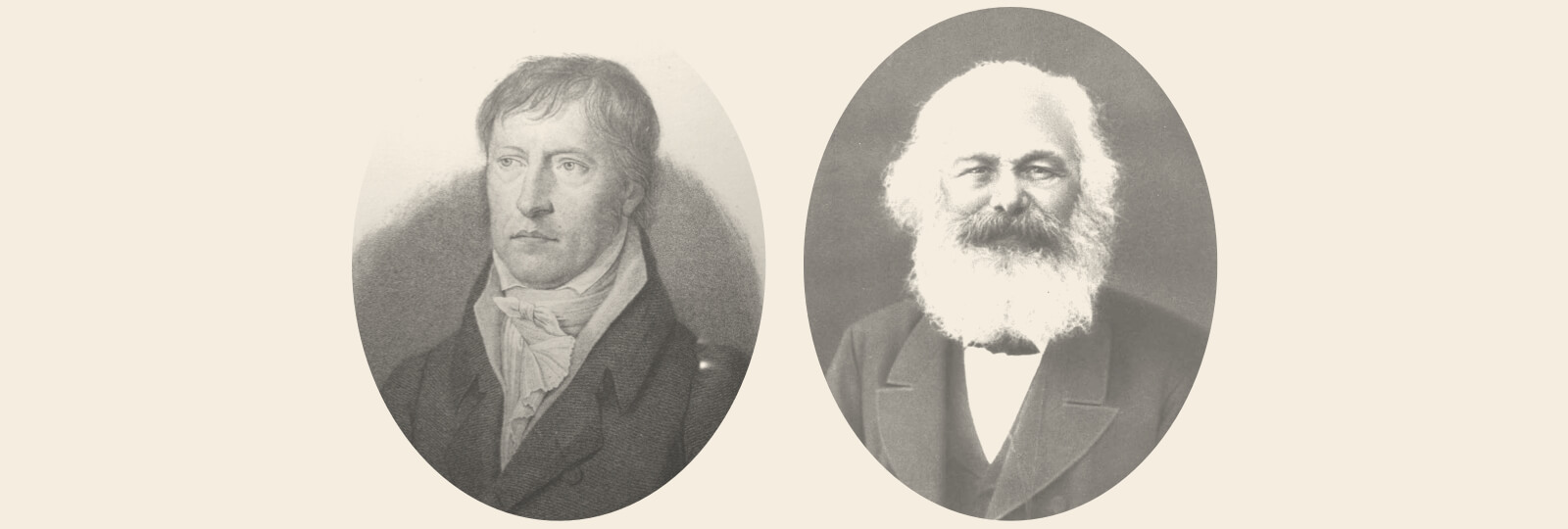

In 1808 G. W. F. Hegel writes an article for popular dissemination asking the question “Who Thinks Abstractly?” His reply – “the uneducated, not the educated… good society does not think abstractly because it is too easy, because it is too lowly.” 1

For those unfamiliar with the usage of concrete and abstract in Hegel (or in Marxism), the response might serve as a shocking inversion of how popular consciousness conceives of the relation between abstract and concrete thought, and subsequently, between the types of people who think concretely and abstractly.

The philosopher is often thought to be the one that thinks abstractly, contemplating things far away from what is thought to be concrete or sensually immediate. Plato’s analogy of the philosopher as a ship captain condemned for “stargazing” is the archetypical imagery for this stereotype. 2

What then is meant by abstract thinking? And why is it so ‘lowly’?

One thinks abstractly when they allow themselves to pass judgement on facts in a manner which severs facts from the factors out of which they emerged. It is factors which allow facts to be facts (the reverse is, of course, also true).

When we take things directly as we experience them and ask no further questions about the plethora of factors which created the conditions for the thing directly experienced, then we are thinking abstractly.

Common sense has a saying for this mistake: ‘never judge a book by its cover’. The message here is clear – doomed to error is the judgement passed on superficial appearance. 3 A boxing judge cannot appropriately judge if they arrive to the fight in the 12th round. Likewise, a fact cannot be properly understood without knowledge of the determinations that allowed it to arise.

For instance, Hegel looks at a murder and says that,

One who knows men traces the development of the criminal’s mind: he finds in his history, in his education, a bad family relationship between his father and mother, some tremendous harshness after this human being had done some minor wrong, so he became embittered against the social order — a first reaction to this that in effect expelled him and henceforth did not make it possible for him to preserve himself except through crime. — There may be people who will say when they hear such things: he wants to excuse this murderer! 4

Setting aside the impressive, century-early psychoanalysis of the person who committed the murder, Hegel’s point is that context and history are ever-present in everyday affairs. The amputation of a thing or an event from the history and interconnections out of which it arose makes the genuine comprehension of that thing or event unfeasible.

On the other hand, concrete thought is present when the thing or event under examination is treated comprehensively, in its development and interconnections. It is here wherein truth lies. As Hegel says in his Lectures on the History of Philosophy, “the true is concrete… [and] the concrete is the unity of diverse determinations.” 5

An almost identical statement is repeated in the famous section on “The Method of Political Economy” from Marx’s Grundrisse, where he says that “the concrete is concrete because it is the concentration of many determinations… [a] unity of the diverse.” 6

Herein lies the difference between abstract and concrete thought. Abstract thought is comfortable with examining things divorced from their determinations, that is, from the dynamic (both immanent and external) factors which produce things. This form of reified thinking kills, it sucks the living spirit out of things and treats them as dead entities.

Concrete thought, on the other hand, seeks to know things in connection to the relations and developments which produced it. Nonetheless, it can never start with that which is most concrete. When it attempts to do so it merely fondles an “imagined concrete,” a deceiving abstraction dressed in concrete clothing. 7

Concrete thought, instead, must be thought of as a process of ascension from the less concrete (the most abstract), to the most concrete. As Marx says, the “reproduction of the concrete by way of thought” is “not a point of departure” but the result of “a process of concentration.” 8

Concrete thought, then, contains abstract thought as a necessary moment in its ascension towards the concrete reproduction of the concrete. However, it overcomes this abstract immediacy by gathering the plethora of determinations which a thing presupposes in a manner which reproduces in the mind the active relations these determinations have with each other within a given totality.

The dialectical method is precisely this – the method of the ascension from the abstract to the concrete. It is, as Hegel wrote, the “soul of all knowledge which is truly scientific,” and as Marx said, “the scientifically correct method.” 9

This does not negate the fact that the ascension towards the concrete reproduction of the concrete in thought is itself a process of mental abstraction. In the same way great joy produces tears and great sorrows smiles, this process of abstraction bears as a fruit its opposite – the concrete.

As Evald Ilyenkov eloquently states – “the ascent from the concrete to the abstract and the ascent from the abstract to the concrete are two mutually assuming forms of the theoretical assimilation of the world… each of them is realized only through its opposite and in unity with it.” 10

Nonetheless, the antipode which ascends from the abstract to the concrete is the dominant, and hence, ‘scientifically correct’ one. Its opposite – the ascension from the concrete to the abstract – is a necessary mediation for the ultimate theoretical goal of reproducing the concrete concretely.

In sum: concrete thought, the ultimate result of the dialectical ascension from the abstract to the concrete, reproduces in a comprehensive manner for the mind the complex movements and interconnections in which all phenomena in nature and society are embedded. In so doing, it provides the most scientifically apt method for understanding the world.

Marxism, however, also serves as a guide to action, as an outlook which seeks to change (as opposed to merely interpret) the world; hence, the dialectical process of attaining a concrete reproduction of the concrete is always grounded on and aimed towards revolutionary praxis.

Originally published on MidwesternMarx

Footnotes

- G. W. F. Hegel. “Who Thinks Abstractly.” In Hegel: Texts and Commentary. Edited by W. Kauffman. New York: Anchor Books, 1966., pp. 462.

- Plato. Complete Works. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1997., pp. 1111.

- This excludes, of course, a dialectical way of thinking about appearance, which sees appearance not as a distortion of essence, but each in an “essential relation” to each other – “what appears shows the essential, and the essential is in its appearing.” G. W. F

F. Hegel. The Science of Logic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015., pp. 419. - Hegel. “Who Thinks Abstractly.,” pp. 463.

- G. W. F. Hegel. Lectures on the History of Philosophy Vol. 2. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1974., pp. 13.

- Karl Marx. Grundrisse. London: Penguin Books, 1973., pp. 101.

- Karl Marx. Grundrisse. London: Penguin Books, 1973., pp. 100.

- Karl Marx. Grundrisse. London: Penguin Books, 1973., pp. 100.

- G. W. F. Hegel. Logic: Being Part One of the Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences. Oxford: Clarendon Press. § 81.; Marx. Grundrisse., pp. 101.

- Evald Ilyenkov. The Dialectics of the Abstract and Concrete in Marx’s Capital. Delhi: Aakar Books, 2022., pp. 139.